Interview: Eddie Howell on "The Man from Manhattan," working with Freddie Mercury, and soldiering onward despite getting the shaft from the Musicians Union

Howell was on the cusp of a huge UK hit in the '70s when he was suddenly informed that his single was to be completely barred from any future play. This is his story.

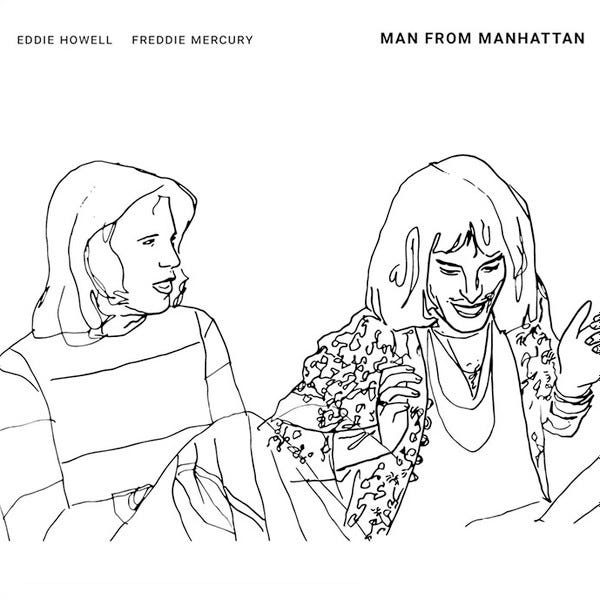

If you’ve never heard of Eddie Howell, well, it’s your loss, but it’s also not so terrible surprising, given that it’s fair to call him a singer-songwriter who's flown a bit under the radar throughout his career…except for one moment in the ‘70s when he almost broke big. It’s that moment that’s effectively the reason he and I had a conversation earlier this year, as it’s taken him until 2024 to finally be able to reissue the song that was almost a hit for him in the UK - “The Man from Manhattan,” which features Freddie Mercury and Brian May - and the other material that he was writing and recording around the same time.

“The Man from Manhattan” was, in fact, a top-5 hit in Holland, and it was on track to be a smash in the UK as well, but as Howell detailed in our conversation, there was an issue with a musician who performed on the song who - as it turned out - wasn’t legally allowed to work in the UK, and when the Musicians Union discovered this, they effectively killed the song, keeping it from any further play or promotion.

Yes, it sounds awful. But it’s true. Fortunately, there are some far less traumatic tales within this conversation, including his time with Mr. Mercury, a close encounter with a couple of Beatles that involved the Kinks, and more.

Read on…and absolutely do press “play” on “The Man from Manhattan.” For better or worse, it absolutely, positively sounds exactly like you’d expect a song featuring Freddie Mercury and Brian May to sound, but it might also spur you to investigate more of Howell’s work, and that would certainly be the best possible outcome to this piece.

It's a pleasure to talk to you. I was absolutely fascinated by your story when I got the press release about it, and I literally had never heard "Man from Manhattan" until then...and I was astonished when I did hear it, because it's so much up my alley, in terms of my taste in music, that I couldn't believe that I'd never heard it.

Eddie Howell: Is it really? Are you listening to the remixed, remastered version?

Yes, they sent me the link to the website so I could check it out.

Oh, perfect! So it's right up your alley, great!

For sure. The singles from Queen's The Game ("Another One Bites the Dust" and "Crazy Little Thing Called Love") were part of my first real indoctrination into music, so they've been one of my favorite bands for most of my life.

What's your favorite Queen album, would you say?

Honestly, I'd probably say The Game, just because it was my first, so I'm most partial to it, but I do really love A Night at the Opera as well.

I was talking to somebody about that. I mean, I'm a Beatles nut. When I heard "Please Please Me," that was it as far as I was concerned. Game on. I played it for weeks. And I think I was round about 12 or 13 then, which is when you're so receptive to music and whatever else is happening in your life. The music that you hear then, it sticks. It'll always stay around. Don't you think?

Oh, for sure. And when I was 12 or 13, that was right as MTV was taking off, so a plethora of new British artists were arriving on our shores. The second British invasion, as the press called it.

Who was part of that?

Duran Duran was certainly the leader of the pack.

Oh, yeah, of course. There's a great British band - I'm sure you know them - the Kinks, but they never really cut it too big in America for some reason. It's very English, I suppose.

What's funny is that I became a fan of the Kinks because of MTV, because "Come Dancing" was a big hit in the US in the '80s. That's actually what introduced me to the band, and then I went back and discovered their earlier catalog. I'm a huge fan of The Village Green Preservation Society.

Really?! Wow! Well, coming from an American, that's quite novel! I love their early stuff. I had an eargasm the first time I heard "You Really Got Me." It was just so brilliant...and simple! And "Dead End Street." Do you remember that one? [Singing.] "There's a crack up in the ceiling / Dead end street, yeah / Dead end street, yeah." I mention that because that was the catalyst, musically, for "Man from Manhattan." [Picks up guitar and proceeds to prove as much.] You know, the same kind of mood. But, yeah, I love that song. He's a great writer. He's got to be about 80 now, I think. All these guys, they're in their eighties, but they're still doing it. It's amazing!

Well, I've read your story on your website, but I'll still ask what I usually refer to as the obligatory secret-origin question: how did you find your way into music? I know that your parents had music playing from an early age, so I'm sure that didn't hurt.

Yeah, my dad was a little bit of a poet and a singer. If there were any family parties, he'd always find his way up after a couple of beers, and he'd hog the stage and let nobody else up, singing these Frank Sinatra songs. I didn't like Sinatra then, but now I love the guy. Now I've grown up, I can see how talented he was. But, yeah, he was always up on stage whenever he could be, doing his vocalizing, and...he had an offer. Have you heard of the London Palladium? Well, they wanted to audition him. I come from Birmingham, which is in the Midlands, and they wanted him to come down to London to audition, which was a big deal back then. I don't know how they heard him or if somebody said something, but...my mom wouldn't move. She would not move out of Birmingham. So she thwarted his career. I don't think he ever forgave her.

But, yeah, I suppose it's from my dad. He always had loads of nice records around, loads of good stuff. Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Louis Armstrong, Sinatra. So I grew up with some nice music around, and every weekend he'd disappear to a little room we had in the house, he'd have his beers lined up, and he'd sort of drink his way through about five hours of constantly listening to music and... [Yells.] "Ed!" He'd call me like that from the other room, and I'd be, like, "Oh, God..." [Laughs.] "Yes, Dad?" "Come and listen to this!" So he'd put Sinatra on - "Nancy with the Laughing Face," I think it was - and he'd say, "Listen! Just listen to the timing!" And now I understand what he was talking about. He was a little bit of a connoisseur. Anyway, I'm waffling on, but I suppose that's where I sort of picked it up from: my dad.

And you said that hearing the Beatles was a transformative moment for you personally.

Yeah, "Please Please Me" was. I was in a youth club somewhere, and there was a little bit of dancing going on, and I just heard this record and... [Sighs contentedly.] I played it for days and days and days. I looked and studied the thing and smelled it, as you do, and saw "Lennon / McCartney" on the record, and I thought, "Did they write it as well?" You know, because in those days bands weren't singing their own songs. It was always the same kind of formula. I don't know if you know Cliff Richard...

I was actually just going to offer him as a possible example.

Yeah, exactly. He was around about that time in the '60s, and he was the personification of what was going on musically. A good looking chap, trying to sound like Elvis, but failing miserably. [Laughs.] I'm sorry, Cliff! And everybody was like that. And they all followed each other, as they do still today in the music business. And then, like a breath of fresh air, this incredible song, "Please Please Me," and this incredible production just blasted out over the airwaves and... [Sighs contentedly again.] It just vindicated my feelings about everything. I mean, it really was game-changing for me, a real watershed moment. But I suppose that's because I was kind of already tuned into music in my youth, so I was receptive to it. And I liked it. I didn't know why I liked it, but I did.

I used to go to this youth club when I was 11 or 12, something like that, and they were all doing the table tennis or darts or whatever else they played, and I found this tiny little piano in this annex room, it was all out of tune, but I kept gravitating towards the piano. I didn't want to play table tennis or chat the birds up. And I remember one day the club youth leader, he came in and saw me playing, and he said, "Oh, Edwin, have you had lessons, then?" I said, "No!" But that day, I was walking on air. I thought, "I must be good or something if the guy thinks I've had lessons!" And that's kind of how I started doing it. But I think it was around "Please Please Me" that I just fell in love with the idea of composing songs. Just a flash of inspiration, I think it was. "I want to do that!" But I think I've always been a bit like that. I like football, but I'm not keen on watching it. I'd rather play it. And I love music, but I don't want to sit around watching it all the time. I want to do it!

So that was it. My dad had a shop with my uncle that had a bookmaker's - like a betting shop - in Birmingham. And my dad used to say to me, "Don't worry about school too much, 'cause as soon as you leave, you're gonna come and work with me," stuff like that. And I was worried about this for quite some time. Finally, I went to my mom when I was about 14 and said, "I'm gonna really disappoint the old man, but...he wants me to work at the shop, and I just don't want to know about it! I know what I want to do." And she was great. She bought me a guitar! Because I knew I wanted to do music. One way or the other, I knew I'd be doing it. And I think you're very lucky if you can even just make a living out of doing something you really like doing. So many people don't really like what they do. They're doing it purely for the money. And that's kind of sad, really.

So your first single was "Easy Street," with "Judy's Gone" as the flip side, although I don't know which was actually the A-side and which was the B-side.

Wow. Well, that's a first. Nobody's ever asked me about that. Blimey! [Laughs.] Yeah, it was "Easy Street," and "Judy's Gone" was the B-side. That was on Parlophone, and it was an independent producer. It was kind of a duo thing with Rob Blanch, a great guitar player. A Simon and Garfunkel-ish kind of duo, we were, and I was writing the songs. That's about the time I was coming down to London to try and get a publishing deal. I produced and made little demos of my songs on a little Grundig tape recorder. My mother would wrap it all up in silver foil, I remember, because...I don't know if it's still the same today, but if you took magnetic tapes on a tube train, it could very easily affect the magnetic oxide of the tapes. So I used to go in and give these A&R people this box with my mom's silver cake foil...and I didn't get anywhere! I was doing that for at least a year.

God knows how I met this guy John Palk, but he was a big fan of a very famous music producer called Mickie Most. John wanted to be a music producer, so I played him "Easy Street," he loved it, he paid for a little session, and Parlophone put the thing out. So you're quite right, that was the first thing. And "Julie's Gone" was the B-side. But they were my songs, and I had my name in the writer's credit, so that was really a success, just to have gotten that, even if it went straight down the charts. [Laughs.]

How did you first come into contact with Freddie Mercury?

I'd better condense it, because it's a big jump. I eventually got a deal with Chrysalis. They signed me up. They'd come up to see me play in Birmingham, gave me some money, I brought my wife and my kid down from Birmingham to London, and I was writing songs as, like, a staff songwriter. Whoever wanted a song, we'd write a song. Cliff Richard wants a song? Okay, what kind of song? Y'know, just doing it like a professional staff songwriter. I'd try and tailor-make a song for all sorts of people.

But I didn't really have much success at doing that. And the head of the publishing company, a guy called Nigel, came up to me and said, "Eddie, y'know, we've signed you because of your songs and your demos. That's what we like. Why don't you record them yourself?" And it's because that's not what I wanted to do. I'm a writer. I'm a backroom boy. I don't want to perform particularly. I was never that confident in my vocal ability. I was never extroverted enough. I remember seeing Mick Jagger for the first time, and I was scared shitless. [Laughs.] I thought, "He's a great performer! I could never do that!" So I wasn't interested.

So I said, "Well, I'm a bit reluctant to do that..." But he said, "Well, look, I'll introduce you to a few potential managers." So I met a few people, and then I met a guy called David Minns, and we got on really well, and he said, "Leave it with me, I think I'll get you a recording deal." So I said, "Good luck!" Not thinking for a minute that he would. [Laughs.] And about two weeks later, he got a choice of Dark Horse Records, which was George Harrison's record label, or Warner Brothers. I couldn't believe it! So I chose the Warner Brothers option. That's where it kind of started.

I'd met a guy at Chrysalis called Robin Lumley who was a great keyboard player. He formed a band with Phil Collins from Genesis called Brand X. So I met Rob there and decided to bring Rob over to produce my debut album for Warners, and I used the whole of Brand X: Phil Collins played drums, John Goodsall played guitar, Percy Jones played bass with me. But with hindsight, in retrospect, they were totally wrong. [Laughs.] These guys... Brilliant players, individuals, fantastic. Percy Jones, wonderful bass player. And Phil... I mean, you know, great drummer. But he was wrong. Because my songs were straight-ahead simple. And let me just say that Percy Jones, if you can play 10 notes in one bar, he'd prefer to play 10 rather than two. So it was all a bit jazzy and it was all a bit busy, musically, and I think the songs on that suffered. But it was a great experience, I suppose, looking back.

So that was the first album, and then David Minns, he mixed with the music business elites. He was good friends with John Reid, who was managing Elton John at the time. And John Reid had just taken on Queen for management. I think before that they were with Sheffield, maybe? I'm not very good with the history, but I think they were. Anyway, so I think David met Freddie in the offices of John Reid one day, and...just to skip ahead a bit again, we arranged to actually perform the album at a club in Kensington, in London, to showcase it. And I had Phil Collins playing congas, and...I just remember that I was on about the second song - the place was full of journalists and music business people, it was quite packed, Warners had done a good job of filling the club - and I looked across the room, and who should walk into the club but David Minns...late. [Laughs.] He was my manager, he was supposed to be there! But he had somebody with him who looked like Freddie Mercury. Of course, the closer he came, I realized it was Freddie!

So I found myself sitting there with Phil Collins on my left playing congas, and Freddie on the side of the stage, leaning on his elbow, listening. I thought, "No pressure, then!" And as I said, I'm not even a performer. I write the things, I don't like performing them, so I'm really self-conscious about it! But I managed to stay around, and as soon as the gig had finished, David Minns came up to me and said, "I want you to meet Freddie!" So that was basically how we met, although I'd apparently seen him before at some restaurant. I don't remember it myself. So as far as I can remember, for all intents and purposes, that was the first time. It was certainly the first time I'd met him properly!

When I listened to "Man from Manhattan" for the first time, I couldn't believe how Queen-esque it sounded...although to be fair, when you've got both Freddie Mercury and Brian May involved, of course it's going to, at least to some extent.

Yeah! Well, you know, we played "Man from Manhattan" in the set. It wasn't on the album that I'd just made with Warner Brothers, but I think I'd made a demo, and I think David must've played Freddie my little two-track demo, because Freddie said, "I really like your song 'Man from Manhattan.'" And I said, "Oh, thank you!" He said, "I'd like to produce it!" I was like... [Uncertainly.] "Really?" And I was slightly reticent, because I envisioned that it was going to end up sounding like Queen. I didn't even know Brian was going to be playing on it at the time, but Freddie's got such a definitive way of working and a definitive style that you're gonna sound like that. It's a way of working that's quite unique that he had back then. A lot of people have copied it since, but it's a very meticulous sound.

So we had a little chat there, and then Freddie decided that we were gonna celebrate. Because he always wanted to celebrate. [Laughs.] So I remember him saying, "Come on, dears, we're going to this restaurant..." It was on a boat! And there were loads of people. But we were sitting around a huge table, and I remember Freddie standing up and picking up his glassy of bubbly and saying, "I just want to propose a toast to Eddie. It's his night!" And I thought, "Wow, that's really nice. How sweet!" And he was a lovely bloke. I really liked him. He was very kind-hearted and generous of spirit and all that. I'm not just saying that.

So from there we started to work on "The Man from Manhattan." We used to go round to his... He had a little flat just around the corner from me. I'm in Notting Hill. He lived in Holland Road, which is about 10 minutes away, with Mary, who was his girlfriend at the time. And we used to rehearse "The Man from Manhattan" there. And this little room was dominated by this beautiful grand piano. I remember the first time I ever walked in, and he'd learnt the song. He knew the chords and everything. Because I could hear it, and I was very slow walking in. But I was really happy, because he'd got the feel absolutely right.

We wrote on it in earnest, and we used to go to the studio in his chauffeur-driven car, because he'd just started to make some money then, and the first thing he was going to get before a bag of chips was a chauffeur-driven car. [Laughs.] Because he's Freddie Mercury! And he had this little cassette machine, I remember, stuffed with ideas for the song. All these backing vocal phrases... I thought, "Great writer at work!" But he loved it. He loved music. He was always happy when he was around music. So we got to the studio and started to work on the song with two guys: Barry DeSousa, the drummer, and Jerome Rimson, a Black American bass player from Detroit who Freddie loved and brought him over to play.

We spent about three days in the studio, and then Brian May came in to do the solo. It was all quite an enlightening experience for me, because I was just a kid from Birmingham. It was just a few ago, so it seemed, that I'd been living in a little caravan with my wife and kid, wondering how the hell I was even going to promote my songs. And here I was now working with Freddie! Fate moves in mysterious ways. So we made the record, and there's loads of little anecdotes I could tell you about that, but...it did end up sounding like Queen! [Laughs.] But it didn't matter, because it got a load of airplay. It was fantastic for me.

I couldn't believe working like that, because the first thing I remember working with Freddie is you didn't have to look at the clock! It didn't matter what time it was. Because studio time was really expensive, even back then, but it didn't matter, because it was Freddie. And people came over, big execs from America, not to meet me, but just to meet Freddie. I won't forget that he kept them waiting. They'd just come in from Heathrow to meet Freddie, and maybe they thought they were going to get the red carpet, but no such thing. It was, like, "Freddie!" "Yes, dear?" "We've got the Warner Brothers executives here!" "Oh, we're busy. We're working. We can't see them at the moment!" And they were picking up the tab! But it was inconsequential. Freddie loved to play that game. But the record labels and the people and the execs, they loved their stars behaving like that. It's the old story, like the petulant film stars back in the old days. But that was part of the game that some people liked to play.

The whole thing with the music union putting a stop to the promotion of the single... I just couldn't even wrap my head around that. It was crazy!

I remember walking along Oxford Street one day, just before what you're referring to happened, and I just heard "Man from Manhattan" all the time, blasting through the airwaves. I was pretty positive that within a week or so we'd be in the charts, the way it was going. It was being played all the time on the radio. And when they got to the stage whereby suddenly everybody knew my name, it was taken for granted that it was gonna happen. I thought, "I can't believe this! I'm just a songwriter! This wasn't in the script. I didn't want this to happen. But it's fun!" [Laughs.] And it was a hit in Holland. But in the UK...

David Mimms became Freddie's first boyfriend, and David went to America with Freddie just after "Man from Manhattan" was released in the UK. I wish he'd been here, but he wasn't. But I got a call from him sometime in the morning, and he said he'd just heard that the Musicians Union had banned "Man from Manhattan" from all media, absolutely everything, because one of the players, they'd discovered, didn't have a work permit. Now, in those days,. the Musicians Union were very hot for orchestras, trombone players, session men. They didn't like rock and roll, because they didn't like synthesizers and they didn't like Mellotrons, which emulated and was taking work away from their members, basically. So rock and roll was a bit of an enemy.

To cut a long story short, there's a lot of secret enemies that you develop in this game - and in your game, too, I'm sure! - and there's a lot of people that look at you and pretend to be happy that you're looking good but secretly they're not feeling like that at all and have some sort of vendetta. And you can imagine that Queen have got their fair share of enemies, too. I'm not talking about me having them, particularly, because I was the new kid on the block, but I knew that Queen that their enemies, and... [Sighs.] Somebody reported one of the players up to the musicians union because they knew exactly what was going in terms of not having a work permit...and that narrows the field down, because there were very people who would've had access to that information. So we're pretty sure we know all these years later who did it. But that's what it was: some jealous creep decided to make that call. And the Musicians Union back then, they were only too pleased to do that, because we were rock and roll. So they scored a point. But I just couldn't believe it.

It just seems like a cruel thing to do, because the effect isn't on the musician who didn't have the work permit, it's on the artist whose work they played on.

Absolutely. It was a very callous thing for the MU to do. And I had a letter of apology years later, saying, "Look, they wouldn't behave like that now." But I don't think they have the same sort of power now anyway that they had then.

Thankfully, you soldiered on, and continued to make inroads as a songwriter.

Yeah, I soldiered on. We left Warner Brothers because they wouldn't put my records out in America, because their policy was that if the thing is not a hit on home turf, regardless of the fact that it was banned by the union, then that's it, they wouldn't put it out in America or other territories. So we left. I walked out of there. Got another deal, made a few records, made an album, and stuff like that, but still wrote for other people, and I had a few good covers. And I sustained myself with a band. I got back together with a band, and we were gigging. So I carried on through the years. But I was always determined that maybe one day I'd get a chance to reconcile and vindicate my feelings about "Man from Manhattan" and the songs I'd written and recorded at Warners that went to waste because of "Man from Manhattan." In retrospect, it's probably the worst thing I ever did, recording that song. [Laughs.] In a sense. Because everything else I did was ignored. But even as I say that, I don't believe it. It was a great experience. I'd never want to swap it. It was just one of those things. But I always felt that one day I needed to give it another shot.

It was about 2016 that I decided to make headway with that with Warner Brothers. I was talking to Warner Brothers about negotiating the rights for about six months in this country and not getting anywhere with Warners Publishing. They were really giving me a hard time. I said, "It's an American label, my deal is with America, so I want to speak to a representative over there. A lawyer or somebody." And I was put onto an attorney over there called Tracey Perry, who was great. She was really a breath of fresh air for the music business, which is recalcitrant with lawyers. So she was great...but she wasn't going to give me anything. [Laughs.] She was very nice, but she wasn't going to give me anything.

It took about two years, although not intensely throughout. I got all the contracts I'd ever signed, and I put them onto my computer. I had the Warner Brothers contract, I had the contract with Freddie, and I had them all there. And I used to burn the midnight oil working on it, because I couldn't really pay for lawyers. It would've cost me a fortune! But I kept reading the contracts, and you learn the more you read, and...most of it's bullshit. [Laughs.] I mean, it really is. It's Latin, and it's complicated. But you can ignore a lot of it and get right to the nitty gritty if you have the patience for it. And to cut a long story short, I found a clause...and I could not believe what I was reading, because it said, had my songs not been released in certain territories prior to February 1978, they revert back to me!

And it was early in the morning when I read this, about 2 a.m., and I'd had some whiskey. But I looked at it, and I looked at it again, and...I must've looked at it six times! But sure enough, that clause changed everything, and Tracey couldn't deny it. She wasn't intimate with all of the clauses of the contract, so she didn't know about this, but when I found it, it just opened the gates for my getting my songs and my rights back to "The Man from Manhattan." And it's taken quite a few years to get to this stage, to get it remixed and remastered, and I employed a friend of mine, Andrea, to do the artwork. But we're doing the pressing on our own, and it's expensive, as it is when you do it yourself, but...I just don't want to work with record labels again!

Nor can I blame you for that, given what you've been through.

No! [Laughs.] But I've got a few friends and my son, and...it's really only four of us. But it's great to be able to finally do it! And there's a website, TheManFromManhattan.com, where you can find out all about it. And as I say, I've had a few other artists record some of my songs. We found out a few years ago that the Monkees recorded one of my songs.

I literally had that here to ask you about. I think you completed some sort of pop trifecta by having your songs recorded by Frida from ABBA, the Monkees, and Samantha Fox.

Ah, yes, Samantha Fox. I couldn't believe it! They called me up and said, "Oh, we've got this Samantha Fox..." I said, "Who's Samantha Fox?" [Laughs.] They said, "She's a Page Three girl, and she's got big bazoombas and stuff." I said, "Oh, yeah, okay, then." But seven million records she sold! I only had a track on the album, but it was good! And then the Monkees... Are you a Monkees fan?

Oh, for sure. I was going through your songwriting credits, and I saw that, and I was, like, "I know that song!"

Well, we had to settle out of court, because it was so long ago. The legal costs for me would've been astronomical, so we settled out of court. But Davy Jones, when he came back over from America, he used to drink in the same pub that I did. He liked a pint...and so did I, back in the day! So I think that's how it occurred, but...that's a story for another time, that whole thing.

Well, I'll start to wrap up, but one question just for curiosity's sake: did you stay in touch with Freddie at all after the "Man from Manhattan" sessions?

Yeah, we stayed in touch. We went to a few funerals, a few parties. Myself and my wife, Marietta, went out with him and Mary a few times to this restaurant we always used to go to, and I always remember that as soon as we walked in... Because Freddie looks like Freddie. He's not Clark Kent. [Laughs.] He doesn't hide. But Freddie walks in, and everything goes quiet, and all of a sudden, we're sitting at the table, and champagne starts to come. The waiter comes over and says, "Oh, so-and-so has sent you a bottle of champagne." And again, "Oh, so-and-so has sent you a bottle of champagne." I thought, "Wow, this is stardom, is it? It's fantastic!" He must've gotten used to it, but I never did!

So, yeah, we saw each other, but then we drifted apart because... Well, we didn't, really. David and Freddie got together, you know, and...in the '70s it was very risque still to be gay in this country. But David didn't care. He was quite courageous in that respect, and everybody admired him for it. And Freddie was obviously in a situation where he was living with Mary but...mentally maybe somewhere else? I don't know. But David came along and I think gave Freddie the confidence to be who he wanted to be. He couldn't help but be affected by that confidence from David. But as I say, in the '70s, it was a bit difficult for them. But they were together for round about three years. And then we did lose touch because Freddie all of a sudden went through the roof in terms of popularity. [Hesitates.] Are they your favorite band, Queen?

I wouldn't say they're my favorite band. I'm a diehard Beatles fan, ultimately.

Are you? Oh, wonderful! I was a huge Beatles fan as well, but when I was trying to get a publishing deal, I came down from Birmingham, caught the train, and I went to Apple...and I was so excited just by the fact that I was going to Apple! It was on Baker Street, and I remember I was sitting there, meeting with a guy called Mike Berry, who was the publisher that I was going to play my songs to, and all of a sudden the phone rang. He said, "Oh, Eddie, hold on a minute." And he goes, "Oh? Oh, really? John and Ringo are here?" I can't believe it! And I'm sitting by the door, and there's a crack at the door, and I'm looking through the crack at John Lennon, with a little dog, and I could just see the end of Ringo's nose, I think. [Laughs.] I couldn't believe it! And they went into the next room to meet, and...I know we've mentioned the Kinks before, but they went into the room next to me, and they played "Wonderboy." Great song. They played it one, two... They played it six or seven times! They kept taking it off and putting it back on! That's all you heard, was "Wonderboy." And then they left! I've got lots of little anecdotes like that, but that's a good one!

Okay, last question: what would you say was the most proper pop star moment of your career?

Oh, God... The most proper pop star moment of my career... Well, I suppose... Because "Man from Manhattan" was top three in Holland, we were in a hotel room, on the balcony, and the girls were there... Not many, but enough! [Laughs.] And for a brief moment, maybe two minutes, I felt like a pop star. That soon disappeared. But for a moment I was, like, "This is really good!" I never really took it seriously, though.

Had no idea about this guy, Will. It's quite a story. He seems to have moved onward from all that madness.