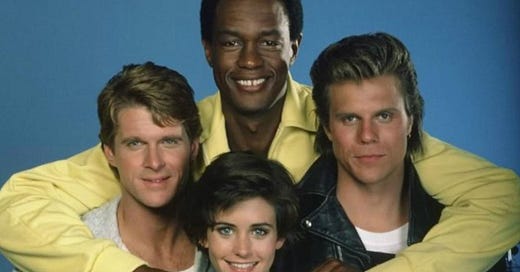

MISFITS OF SCIENCE: An Oral History (Pt. 2)

Missed Pt. 1? You’ll want to read that first, which you can do by clicking here.

Don’t worry, we’ll wait for you.

All caught up?

Great!

Nwo ahead and dive into Pt. 2, and remember…

“When the unusual becomes the usual, the impossible becomes possible, the incredible becomes credible, and the weird gets weirder, who do you blame? The Misfits of Science!”

Filming the Pilot

Mark Thomas Miller: We were at a water treatment plant out in north Hollywood. No choreographer, no anything. Never rehearsed it. I had the flu and was running a fever somewhere around 102, maybe 104, and they pulled me out of the trailer at about 2 AM and said, “Okay, let’s do this. Now, you sing and dance and jump around…” I’m, like, “What…? Really? Should we practice or anything?” “Nah, let’s just go.” I’m, like, “Uh, thanks for the head’s-up on this, man!” I mean, I didn’t go the dance academy, y’know? So I think all of that was shot after about two shots of tequila. I just said, “All right, let’s do it. Just do it and don’t think about it.” The jumping and all that, it was just ski moves, stuff I’d done when I was skiing. I’m, like, “Doesn’t someone want to tell me what I should be doing, or how I should be dancing?” And they’re, like, “Just hurry up. We’ve only got, like, 40 minutes ‘til the sun comes up.” Well, okay…

James Parriott: That was me. I was telling him, “Go. Just go! We’re losing it!” Look, it was dawn, the light was just starting to come up, and we were just so rushed to get that shot before we lost the dark. It was crazy. But he was a trooper, doing take after take after take. And we told him kind of what to do. I mean, I blocked him. But he’s right, I basically said, “You’ve just got to do it, dude.”

Cue the Opening Credits

Donald Todd: The main titles are fun. It’s still kind of…it’s really forward-looking. Jim was forward-looking in many ways, and we fought a lot about that, but it starts off with Bobby Short doing the theme, and then there’s the kicking over of the TV and into the more contemporary version of the theme. He was trying to say, “We’re not doing that show, we’re doing this show, and it’s more hip.” And I remember the people at Universal going, “Why don’t you do it without the TV? We don’t like the TV!” And I don’t think they gave him the budget for it. I think we had to find it ourselves. It’s a really cheap thing, it’s just a guy playing a piano and then a foot kicking over a TV, but it was really controversial, because back then nobody did anything interesting with the main titles. You just showed the characters sliding into frame. But I remember that was pretty cool. And Jim wrote it.

James Parriott: Actually, I wanted to do it without the TV, just with Bobby Short sitting at the piano, singing the theme song. I mean, there’s your titles! But they were, like, “What?” They made me put it on the TV. But Bobby Short survived. At least I got Bobby in there.

Music, Music, Music

James Parriott: Analog is very different from digital, and when you scored something back then, when you put music to a picture, it was done with a real orchestra. And that was its own tension. It was the first time you would see your picture against music. It wasn’t like today, where they send you stuff via .mov files, and you can look at them on your computer and go, “No, I don’t like this. Can you change this? Can you change that?” way ahead of time, before you get on the dubbing stage. Then it was, like, the composer usually just finished the score the day before, and they spent all night long having people copy the parts for the musicians, and then 80 musicians come in to do their thing.

That was its own gut-wrenching but fun day, because sometimes you wouldn’t like what you saw and you’d have to go to your music editor and say, “Can we place those 12 bars, which I hate, with these 12 bars, which I think are good?” Or you’d have to go to the composer and ask, “Can I lose the horns in that section? Can you just give me rhythm there?” And you had to do it all on the fly. It was greatly liberating when digital came out, because you didn’t have to do that anymore, but a little sad, because all the musicians were out of jobs. But in my career, it’s been amazing to watch how digital has changed the business.

The Special Effects

Mark Thomas Miller: I didn’t have to do anything, really, because the special effects were your standard 1980s horrible. Ironically, though, that’s kind of what killed the show, because each episode was still something like a million dollars plus. Parriott could tell you more than I can, but I know we were a million plus back then, and each lightning effect cost, like, thirty grand, or something stupid like that. So that’s why each episode was really expensive. Really expensive and really bad.

Like, if they wanted fake lightning, they had a shotgun that shot these little pellets that kind of exploded, and I remember we had two grips on stepladders behind the camera firing at us. I’m thinking, “This doesn’t look professional...this is not right…” And sure enough, Dino got one right in his eye. Almost took his eye out. Hit him right in the corner of his eye. Bounced off a 45-degree wall and went straight up into his face. Nobody even looked at the wall and said, “Hey, that’s a 45- degree wall we’re hiding behind, so when we stand up, it’s gonna bounce.” Stuff like that was kind of crazy. That’s back when explosions were happening all the time and people were getting hurt. The only guy that really had to sweat it out, though, was Kevin. Kevin would spend weekends doing blue-screen at the studio. He’d put in all that extra time.

James Parriott: The toughest shots were the ones with Kevin, where we, uh, downsized him. Those were tough. You could do that show very well and very easily now, but it was very expensive and very tough then, with the blue screen. It was all analog. And it was not an easy thing to do.

Donald Todd: There weren’t very many special effects, really. I think Courteney…she had that telekinetic thing she did, with the flash cuts, and then things either slid or floated. Basically, we weren’t too much farther than wires and fishing line. In fact, I think those things were on fishing line when she did that.

James Parriott: Some of the stuff we did with wires was pretty tough to watch. My God, we did some really cheesy things. In the pilot, the frozen tunnel is from the Universal tour. If you don’t remember it, I’m not going to try to remind you. We did everything we could do to find effects and make ‘em work, but it wasn’t easy.

Mark Thomas Miller: When I’m singing “Johnny B. Goode” in the pilot, holding onto those chargers…? Yeah, if you look at ‘em, they’re upside-down garbage cans. They’re plastic garbage cans with some PVC pipe coming out of ‘em. Nobody ever figures that out until I tell ‘em, and then suddenly they’re, like, “Omigod, it is a garbage can!” So it worked!

Donald Todd: Mark just had that one effect that went kaboom, and they could put that in there and then just blow something up. Universal was good at blowing things up. There were a couple of things I learned that they did very, very well there. Crashing cars into soft trash, that was one. So you always had cars crashing into soft trash. You’d go down a back-lot street really fast and have a lot of metal trash cans, but you’d only hit a pile of boxes. I learned that, and that you could always flip a car onto its side. They knew how to do these things, and…we had one day of…what do you call it? Second-unit work. The reason I forgot it is that we don’t do that anymore, where we had the day of second-unit work. They called it Seven Plus One, so you’d get seven days of shooting and one day of second-unit work, where you’d flip your cars on the side and such, and being an action show, we had a day of that.

The special effects were just limited to what those characters did and then a few explosions. Small explosions, things in the lab. We didn’t think about those, but Jim did, and he had Alan Levi, our line producer, who was a veteran of the system as a director. He handled all of that stuff, and we concentrated on the writing, and Jim was great at editing. He would rearrange episodes in the edit bay in a way that I still don’t have the guts to do. He’d say, “What if we start with this act and end with that act and move this here?” It was fun for him to do that. But I was so new, and I was way out of my depth. I remember just struggling and struggling to come up with my first story. But he was really patient. Remarkably patient. I’ve tried to learn that over the years, going, “Look, this person doesn’t know what they’re doing, so…” I turned in my first script, I think it was probably 15 pages too long, and I remember going in his office, watching him just make cuts. Cut, cut, cut. I said, “What are you doing to my script?!?” I didn’t imagine that you’d ever be rewritten! But you do. So he rewrote my first script. And I was devastated. But that’s how I learned.

Whatever Happened to the Ice Man?

Donald Todd: We had a character that disappeared pretty quickly, right after the pilot, called…was it Beef? He was played by Mickey Jones, who’s had a great career playing in a lot of things, but he was a guy who had to stay frozen. That’s why we had the ice cream truck: because originally one of the members of their team had to stay frozen or he would die. That’s why we had the ice cream truck. Other than that, there wasn’t a reason for it. But there were just too many characters, and with that one…in the conception of the story, we were, like, “Well, what do we do with him? He’s frozen, he has to stay frozen, so he can’t be outside, so…ah, yeah, forget it.” These things happen as shows develop. Part of it was the budget, but also, y’know, you can’t really tell a story with a guy who’s got to be frozen all the time and just growls all the time, and that’s kind of all he was.

James Parriott: It’s not easy to call an actor in your pilot and tell them, “You’re not coming back.” I know I’ve done it twice, and…I think I called Mickey. I hope I called him personally. I remember vividly when I had to do it for the other two actors, but with Mickey, that was back so far that I can’t remember. But I think I did. It’s just not fun. You hear your series is picked up, then you get that call. So you’re joyful, you’re elated, then you hear, “Hey, you’re not gonna be on it.”

The Ice Cream Truck

Mark Thomas Miller: Yeah, you know, I honestly can’t tell you much about the ice cream truck, because I spent most of my time hanging out of the door! I can tell you that that thing was a piece of crap. Sometimes it’d start, sometimes it wouldn’t. That was another one of those cases where you were, like, “Wow, you guys don’t have two or three of these? You didn’t throw in a new engine or make sure it runs?” They’re, like, “Nah.” They don’t think that far ahead.

Donald Todd: There was only one ice cream truck, and it almost tipped over. In fact, it’s in an episode…I’m pretty sure it’s the Space Shuttle episode, actually, and in an Act 4 that I wrote in one morning. If you’ve ever heard of the phrase “run and jump,” that’s what this Act 4 was, and you could write that pretty quickly, because it was just calling out every shot of action. And one them, I said, “Oh, the ice cream truck skids to a stop and has to do a U-turn.” And they looked at me and said, “Uh, I don’t know about that…” So they gave it a try, and we have a shot—it was second-unit— of the thing almost turning over. I mean, it looks like a fantastic Hal Needham shot, because the camera happened to be right where the thing almost tipped over on it, but it righted itself at the last second. It was not outfitted for high-speed chases.

James Parriott: Yeah, the truck was a little top-heavy.

Donald Todd: I don’t even think you could shoot those shots in the ice cream truck now, because I think all the Misfits gathered into one shot every time they were in a chase in that ice cream truck, which meant they were standing up, holding onto the backs of seats at high speed. You think about that now, where you can’t have an actor even get into a car without having the first thing they do be them reaching for the seatbelt. If you don’t show it, they won’t air it. Well, these people were storming around in an open ice cream truck! I know they always held on, but I still don’t know how we didn’t lose anybody. But the actors seemed to enjoy it. They were always laughing. They had a good time. And why wouldn’t they? They were young, and they were working.

Mark Thomas Miller: What’s funny is that I’ve got an ice cream truck sitting right outside. I just bought one last week! Maybe it was a subconscious thing! I bought a vintage ’63 Ford…well, it’s actually a UPS truck, but it looks kind of like an ice cream truck, and I’m gonna convert it into, like, a rat rod. I couldn’t figure out why I bought it, but maybe that’s why! Maybe it was a subconscious Misfits of Science thing!

Misfits of Science: The Hardest Job You’ll Ever Love

Donald Todd: I remember us working long hours, we wrote long hours…I thought that’s how it always was. You came in at 7:30 in the morning, you left at 8:30 at night, and that was going to be my life, working seven days a week.

James Parriott: When you’re cutting, editing, casting, you’re in production, you’re gonna go home at 9pm. Maybe. Doing 14-hour days was kind of the usual thing.

Donald Todd: One day I was standing on the set somewhere north of L.A.—maybe in Piru, which is where you shoot when you don’t want to look like it’s L.A.—and we were waiting for magic hour. At the time, if you wanted to shoot the sunset at magic hour, you had to shoot it right then. There weren’t a lot of visual effects you could do. So we’re waiting, it’s getting colder and colder, and Burt Brinckerhoff, who was directing this episode, turned to me and said, “You know, there’s a job where you never go outside…” He was referring to sitcoms. And by the next year, I was on ALF, he was on Newhart, and I ended up not having to go outside for the next 15 years.

James Parriott: Yeah, but comedy is hell, too! The thing I don’t like about comedy, but particularly in that era, is that the writer’s rooms would go until, like, two or three in the morning. I don’t know about ALF. I don’t know how those guys did it, but… Look, all I’m saying is that, yeah, you’re inside, but you’re there all the time…and you’re there really late. Plus, for my part, I’ve always liked the film aspects of drama. I have directed some single-camera comedy. During a lull in my writing a few years back, though, I don’t know if you remember the series Action, with Jay Mohr, but I directed an episode of that, and they liked it enough that they signed me up to do multiple episodes. But then they cancelled the show! I had so much fun directing it, though, that I actually found myself saying, “You know, maybe this could be more fun…”

Donald Todd: I remember that time on Misfits of Science fondly now, but at the time it was a massive pain in the ass. When you’re working that hard under that kind of duress with that small a staff…I think everything is stressful! I don’t know if Jim had any fun, but I know you remember it as fun after it’s over. At the time, though, I was thinking, “Is this my life? Am I going to be working seven days a week?” And it turns out that, yeah, it is my life. But that’s only because I do pilots. If you don’t create your own shows, you don’t have to work that hard. But if you create your own shows, you’re always working.

Writing the Show

Donald Todd: I broke in a lot of writers, because that was a time when freelancers got a lot of work, so my job and Morrie’s would be to meet with writers and hear pitches. You almost never do that anymore. The Writer’s Guild has worked hard on that, but it just doesn’t happen, where writers go around and pitch, and you get an episode, you write the episode, and you turn it in. We had to do that a lot, because otherwise the three of us had to write everything.

Dean and I used to joke that his main line was, “Let’s go!” And after awhile, I would write “let’s go” for him into every script, because he would say to me, “Well, when do I say, ‘Let’s go’? We can’t go if I don’t say, ‘Let’s go!’” So I’d write it in there: “Let’s go!” I would love to have cut together a compilation of him saying it, because he easily must’ve said it 40 times in the first 13 episodes. But, hey, that’s what his job was!

I learned to write fast. I remember sitting, writing on a yellow pad on that episode and turning out pages, handing them to my assistant, who would type them and send them to the set. I wrote Act 4 in the morning, and they shot Act 4 the next day. That’s actually something that I never forget, because I learned that I could do it. It’s not the ideal writing, but once you’ve done it…and I did that at the age of 25…you go, “Well, you can do it. If you have to, you can turn it out. It’s not a novel. You can actually make people say things, and they’ll shoot it the next day. So that was a good lesson for me. But we did a lot of that. We had a lot of really good writers in there, but it was a really weird show, and they just didn’t have time to work on their drafts, so they’d turn in their drafts, and we’d say, “Thank you, goodbye!”

I met Michael Cassutt, who ended up writing a few shows. He came in and did a couple of things for us, and he was really terrific. We were always trying to get money to add somebody to the staff, but it just never happened. Pamela Norris was great, too. At the time, I was impressed with Pamela Norris because she lived in the Burbank Holiday Inn. I didn’t understand that, but she pointed out to me, “Look, somebody comes and makes up your room every day, you’ve got parking…” And she sold me on the idea of living in a Holiday Inn! And then over the years I’ve met her a couple more times, but at the time, I thought, “This is fascinating!” I was just learning about this whole world, people I’d never seen before. I thought you had to have an apartment and dogs and kids, and she’s, like, “No, not really. Burbank Holiday Inn.” But she was terrific, and she went on to write some really good sitcoms.

James Parriott: Pam went on to have a really great career. And Mark Jones…I remember Mark because he went on to do Leprechaun. But, you know, that was a different era. You didn’t have large staffs, and it was pre-writer’s room, for the most part.

Hill Street Blues was the first show to really sort of have a writer’s room, and…well, even that wasn’t even really a writer’s room. On Hill Street, what they would do was break the shows apart into character arcs. They’d give you a character…like, you’d do Renko for an episode or two, and all you would do was do the Renko story. And then they’d stitch the stories together. I talked to Tony Yerkovich when he was doing the pilot for Miami Vice, we were in the same suite up at Universal, and he’d come out of Hill Street with a couple of Emmys, and I said, “Must be nice!” And he said, “You know, it’s really as satisfying as you’d think. On one hand, you’re winning an Emmy for the script, but on the other hand, you know you only wrote this one little bit, because everyone else was contributing.” He said it was kind of a double-edged sword that made the Emmys not mean quite as much.

Tonal similarities to Ghostbusters?

James Parriott: You see Ghostbusters, and you go, “Okay, that’s a tone that we can duplicate on television…or at least try to, anyway.” Yeah, it was intentional.

Mark Thomas Miller: I never heard comparisons to Ghostbusters. Was it even out when we premiered? I couldn’t even tell you. I heard Fantastic Four all the time, though. I heard that a lot. But I didn’t know what that was, because I wasn’t a comic book guy.

Donald Todd: I know there were a spate of Ghostbusters-like shows at the time, things that were very specifically trying to do that. I also remember people would ask, “Is it like Weird Science? They’ve both got Science in their names…” But I think it had its own unique tone, and I really do think that ours was just Jim’s love of super powers. He’d done The Incredible Hulk, he’s done The Six Million Dollar Man and The Bionic Woman, so he knew that area. And it was fun. I think the idea was to have fun. Everything that Jim wanted to do was always bizarre fun.

Challenger Challenges

Donald Todd: I was just thinking today about the Space Shuttle episode we did, “Lost Link,” about a primitive man they discover who’s never seen anything, and then he sees the Space Shuttle, and he tries to put a figure that represents his soul on the Space Shuttle so it can take it to heaven. And that episode was scheduled to re-air on a Friday night…and it was that week that the Challenger exploded.

James Parriott: Don used to leave his TV on in his office, and we were there the morning of the Challenger disaster, and from the other office, I hear Don go, “Jim? You’ve got to turn on your TV now.”

Donald Todd: We all sat and watched the Challenger coverage, and then all of a sudden Jim goes, “Oh, my God: that’s our episode!” That’s a vivid memory. A strange tragedy combined with a weird business thing like that…you have to do that kind of thing every now and then. They really had to scramble. Stuff happens that you just can’t imagine would happen more and more frequently, unfortunately, with all the school shootings, and you have to go, “Okay, what have we got in this episode that might relate to a school shooting?” You don’t think of it at the time, because these episodes are done weeks in advance, but then all of a sudden it’s on, and…uh-oh.

Life on the Universal Lot

James Parriott: The Universal lot was sort of magical back then. The first show I did there was Voyagers! and what was great about that series was that we didn’t have to pay for any of that backlot. All we had to pay was reparations. The lot was pretty run down, but I could go back there, and I could go on any set. At lunch, the writers, we’d walk through all the soundstages and see what Features had built, and if a feature had built a set and it wasn’t being used and they hadn’t torn it down yet, you could run down to Production and put a pin in it and write a scene around that location, and they’d leave the set up. They don’t do that now. The feature directors decided they didn’t want their stuff being used twice. But back then, Universal would say, “Sure!” We didn’t have a huge budget, so I’d walk the back lot with the director of the episode, my unit production manager, and my set designer, and we’d literally chalk on the ground what angles we were going to shoot and what lens sizes we were going to use, then how many buildings to paint in the background. But it was fun, because you got to use everything on the lot. When we did Misfits, which was just a couple of years later, we did the same thing. We sort of were able to use what was up on the lot. And it was a lot of fun.

The only bad thing about working the back lot is that every 20 minutes a tram would go through. And now it’s even more often. Now it’s all about the tram. But it goes through, with someone announcing, “And now on your left…” That’s a drag. You have to stop production when that happens. But it was really fun back in the day. There’s no more fun than the Universal lot in the mid- to late ‘70s and early ‘80s. I just had a ball there. I learned so much, and there was so much going on, and…it was a different type of thing.

Doug Hale (Kerry McDermitt in “Three Days of the Blender”): I remember one funny incident that occurred on the set during the week I did the show. Dean and I were standing at a craft services table up by one of the roads that came down on the Universal tour, where all the trams were driven, and it sort of bordered the soundstage that they were mostly set up in with their interior scene stuff. We were up there for some reason or other—it was something to do with the ice cream truck, I believe—and we had taken a break, it was toward the end of lunchtime, and were standing there by the craft services table, just shooting the shit, when here comes one of the trams. It’s not what you’d call loaded up with people, but the guy who was driving the tram and talking about this and that and other in regards to Universal City, he saw Dean and me and other members of the crew, grips and electricians and what have you, just sort of fumble-farting around there, and he mentioned Dean as one of the quote stars unquote of Misfits of Science….and he didn’t know who the fuck I was!

So, anyway, we were standing there, and as the tram pulled up right beside us, we didn’t move, because we were having a cup of coffee or whatever, but some people leaned out of the tram and were urging Dean over to give them an autograph. I’m sure a couple of those people didn’t quite make the connection between Dean Paul Martin and Dean Martin, because, y’know, like I said, he didn’t look anything at all like an Italian from Ohio who used to be a prize fighter! But he walked over and very affably was giving whoever asked for it an autograph.

And then one of the ladies who was urging something into his hand looked at me and said, “Hey! Who are you?” And I said, “My name is Doug Hale.” She said, “Well, I’m sure you’re gonna be a star, too. Come over here and sign my book!” Dean said something to the effect of, “Yeah, he writes better than I do, and he’s taller than I am, too, so he’ll be a star. There’s no doubt about it.” He just started ragging them and me and carrying on a bunch of a shit. So I walked over and signed several peoples’ book as well! Because, y’know, these people are anxious to just…they just want signatures for their collection. You run into that type a lot. That’s why a lot of your more easily-identified names will stop giving out autographs altogether. Paul Newman’s one. He started having people asking him for autographs when he was taking a leak in a public toilet! Reportedly, Newman’s response was, “Well, what the fuck would you like me to sign it with?”

Donald Todd: Being at Universal was a great time. I didn’t know it then, but you learn things while you’re there…like, for instance, the tram never stops. The most money the studio ever got at the time was on their tour, so they would cancel your show before they would cancel the Universal tour. So you’d just call “stop,” and the tour would keep going. Those are little economic lessons that you learn. Now I’m on a CW show here on the Warner Brothers lot, and CW shows don’t have much money, the budgets are low, and we can’t have overtime. It’s very much like shooting at Universal. Universal used to have a guy who would stand on the set about a half hour ‘til wrap and look at his watch, and he pulled the plug—I mean, sometimes literally pulled the plug—at 12 or 13 hours. And then, over the last few years, that just kind of went away, and people would do 16-hour days.

But here on this Hart of Dixie show I do, we pull the plug after 12 hours. And that was really good experience. I think about it almost every day, think of how we used to do it. And it was a good idea! You can’t do great work sometimes when people are exhausted and the budgets are so high, so we do our best, and you get out, and you make it work. That’s how you teach people. You don’t give ‘em an unlimited budget. You give ‘em a small budget. And that’s what we had. I would’ve never learned what I learned if we’d had a big budget, a big staff. I would’ve just been lost in that group. With this, they say, “Look, you’ve gotta go make this show.” And you do. You make the show. It wasn’t perfect, but it worked pretty well.