Pilot Error Revisited: Kevin Curran's CIRCUS (1992)

Several years ago, when I was a contributor to the sadly now-defunct website Antenna Free TV, I created a column called Pilot Error, where I looked back at TV pilots that never actually made it to series. When the site came to a conclusion, so did the column, but thanks to the kindness of the other folks involved with AFT (it was very much a collaborative effort), I’m able to bring them back to life here on Substack.

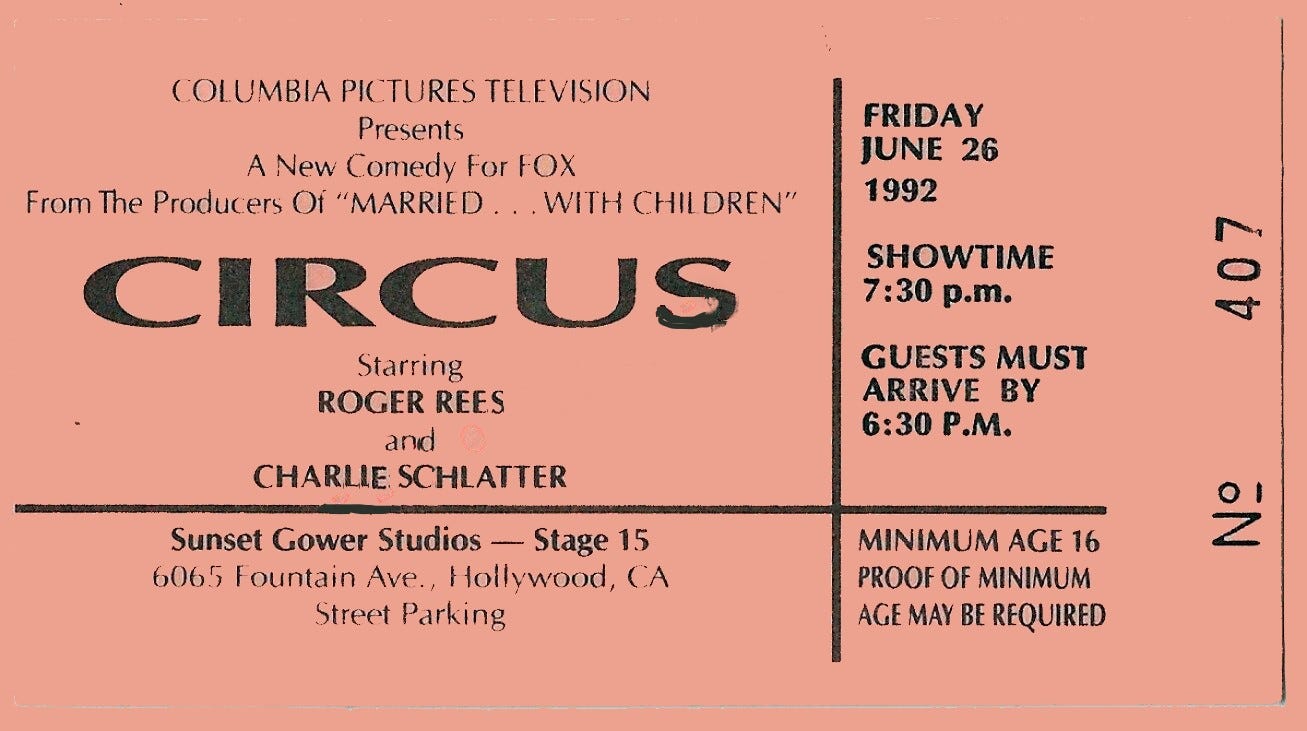

CIRCUS (1992)

Starring: Roger Rees, Charlie Schlatter, Lisa Edelstein, Kim Walker, and Philip Baker Hall

Y’ever heard the one about the network executive who said “Nelson” when he meant “Hirsch,” and the executive producer whose reaction to the error lost him a series?

If you’re a TV writer, you may very well have, as it’s a tale so tremendous that it seems as though it must surely be apocryphal, especially since it’s one that always seems to appear second-hand. The story first seems to have made it into print in a 1992 article by Laureen Hobbs in the late, great magazine Spy, and it was later offered up by John D. Brancato as part of his contributions to the book Tales from the Script: 50 Hollywood Screenwriters Share Their Stories. Brancato managed to deliver the punchline to the story without naming names or even citing the project, but Hobbs was somewhat less discreet, so it’s not like the identity of either is difficult to find…if, that is, you know the right words to Google.

The pilot was called Circus. The executive producer was named Kevin Curran. You may not be familiar with the former, but if you’re a Simpsons fan (or a Late Night with David Letterman fan, or a Married with Children fan), then there’s a good possibility that you recognize the latter. Thanks to one of his fellow Simpsons scribes, I was put in contact with Curran, who—for the very first time since the shit went down lo these many years ago—agreed to tell his Circus story on the record.

The punchline to your experience with Circus is well-documented amongst TV writers at this point, but that’s really the only bit about the pilot that’s made the rounds, so I was hoping you could help fill in the blanks a bit. First of all, what was the premise?

Well, it’s interesting that I later ran into trouble with the premise, even though it stayed exactly the same as it had been when FOX bought it, but…it was about an alcoholic misfit clown and a bunch of other misfits at a circus, and then a young wannabe clown who was kind of innocent. And there was a bitter dwarf, a drunk fortune teller, and, y’know, these kind of shady characters. At the time, FOX was doing these things called presentations—which was like a staged version of the show, where they wouldn’t film it—and based on that, they picked it up for six episodes.

If I’ve got my timeline straight, then Circus would’ve been made right around the same time as Shakes the Clown, correct?

Yes! [Laughs.] Yes, exactly.

That’s some incredibly bizarre parallel evolution.

I actually don’t remember which pre-dated which, but the original inspiration for Circus was a sketch that was on (Late Night with David) Letterman—‘cause I used to work on Letterman—called “Flunky the Clown,” where Jeff Martin was this cigarette-smoking bitter clown.

Was the presentation actually done with the intended cast?

Yeah, it was mostly the people who made up the cast. I mean, as with many pilots, there were some replacements. It was actually easier to replace cast members when they did presentations, because the original actors weren’t even on film! [Laughs.] So that was probably in January of 1992 that we did the presentation. But by the time May or June rolled around, of course FOX had completely forgotten what the show was about, because they had no physical reminder at all.

All they had were their spotty memories from the presentation about what it was. At that point, it became a really grueling process where, at one point, there were all these censor notes, and they’re saying, “Well, there might be a slot open at 8pm, so it has to be a family show.” [Laughs.] It’s a show about an alcoholic loser clown! He’s the main character!” I mean, that’s not really very helpful…

Yeah, that really screams “family-friendly comedy.”

[Laughs.] Yeah! So there were unusual tribulations like that, and there was…I’d say there was a breakdown in communications between the different people, like Columbia and FOX and myself. And I was very much committed to doing the show that I wanted to do, and they were very committed to, y’know, whatever they thought of that week. [Laughs.] So we started filming in June or July, and we had done the pilot plus two episodes. We’d just done the table reading for the fourth episode, and it went really well. You know, the cast and crew, they were having a really good time, and it wasn’t that hollow, false laughter you hear so often. It was really legitimate amusement. But the FOX and Columbia people decided they’d had enough. They were not going to smile at all, and they marched in just like a military court, really. It was just a very frustrating experience.

So what happened was, the guy who was the vice-president of FOX, he and I were talking, and he said, “You know, we have serious problems with the show, and we don’t think we’re going to pick it up beyond six episodes.” And I said, “Well, that’s interesting, because it is the show that you bought.” And he said, “Well, we don’t want that anymore!” And what happened then was… There was one moment when he said something, and I was trying to think of an answer, so my eyes kind of drifted. And he said, “When I talk to you, I want you to look me right in the eyes!” And…I came very close to picking up a television and clobbering him over the head with it…and this was when televisions were, like, 400 pounds. [Laughs.] But I didn’t do that. And the discourse became more civilized, as we were trying to figure out what exactly we could both live with and what kind of compromises would have to be made by both parties.

So we’re going along this route for awhile, and…they still weren’t pleased. [Laughs.] I mean, they really weren’t pleased. They were not cracking a smile. It was like they’d been done an injustice by the show. It was, like, something about this poor little innocent show they saw as like having a gauntlet hurled at them. So, anyway, we’re talking about different ways to do the show, and one of the vice-presidents of Columbia said, “Well, I think you’re spending too much time on the minor characters. You should spend more time on the two main ones.” And I said, “Well, if you look at a show like Taxi, each of the first six episodes, the main story was about the main character, but the B story sort of introduced different members of the cast.” And then this guy said, “Well, there’s a difference: Taxi had Judd Nelson.” And I said, “It was Judd Hirsch, you fucking moron!” And then everybody kind of looked at their shoes. And then they just got up and left. The boat had, uh, pretty much sailed with that. The next day, we came in and they were taking down the lights and packing up the entire show.

Just to clarify this scenario, exactly what was your inflection when you said, “It was Judd Hirsch, you fucking moron”? Was it in a “ha, ha, how silly of you” sort of way, or was it angry?

Oh, no, it was angry. [Laughs.] It was definitely angry. I’d just reached my breaking point. Yeah, the vice-president of Columbia sort of got what was deflected from the vice-president of FOX when he said that “look me in the eyes” thing, which really, really got under my skin. But I let that pass, so the explosion had a lot more to do with that. I mean, it was just someone making a simple mistake. In fact, not even a mistake, just a misspeaking!

So who was set to be in the cast of Circus?

Oh, Roger Rees was Kelso, the alcoholic clown. And there was Philip Baker Hall, who was the owner of the circus. There were other people who weren’t as famous. Kim Walker, who was in Heathers, was the lead girl, and there were different clowns played by John Nesci and other people. Yeah, it was a really nice cast, a really nice show. Everyone really kind of liked each other and was on the same wavelength.

If you were doing the table read for the fourth episode, I presume you had a writing staff by that point.

Oh, yeah, we had a writing staff. We did the presentation around January, and we put together the writing staff somewhere in June.

Who was on the staff?

Well, the most famous person is Greg Daniels. I believe that was his first sitcom job, if I’m correct. I know he wrote on SNL, and then…I think he did a show out in Los Angeles, but I don’t believe it was a sitcom. Yeah, he was an executive story editor at the time…and he has wildly surpassed everyone else involved with this tale. [Laughs.]

What was the reaction from everyone else involved with the show when they found out the reason why the plug had been pulled? Or did they just kind of accept that, because of how the network felt about the show, it was always going to be a short-timer, anyway, and move on without issue?

The immediate reaction of the other writers who were in the room was stunned silence. Everyone kind of looked down into their notebooks. As far as the writers were concerned, within weeks three of them—Jace Richdale, Greg Daniels, and John Collier—had joined The Simpsons. Maybe (the title) Circus wasn't too far off the mark. The production staff was kind of shocked, but they knew there had been a lot of squabbles. I think one of our PA's summed it up best when he drew a kitchen pot on a chalkboard with the single line, "Too Many Cooks."

So what did you think when word about the punchline of the story, as it were, started to make the rounds?

Oh, I was very proud of it. Whenever writers hear it, I’m momentarily their hero. Because, y’know, you have to put up with so many contrary and ridiculous network and studio notes, and you just have to kind of swallow your pride and do it. This time, it was, uh, a little bit of a different ending. [Laughs.]

Yeah, Michael Price is the one who suggested that I talk to you about your experience with Circus, but I didn’t really know what the experience was until Bill Oakley Tweeted me the advice, “Go and Google the words ‘It was Judd Hirsch, you fucking moron.’ The first three hits will tell the tale.”

[Laughs.] That’s right!

And yet all those hits involved someone else telling the tale. So you’ve never gone on record about the experience before?

No, I haven’t, actually. It was written about in Spy Magazine, but I didn’t participate in it. This is actually the first time I’ve ever actually said anything about it myself. So you’ve got an exclusive about a failed sitcom from 1992. Congratulations! [Laughs.]

When Curran mentioned that Philip Baker Hall had been in the cast of Circus, I immediately made a mental note to myself to drop a line to Hall’s publicist as soon as I got off the phone, as I’d done a Random Roles interview with Hall that had gone particularly well and thought there’d be a decent chance that Hall might be willing to hop back on the phone to discuss this one-off. In fact, if I had any concern, it wasn’t that he’d decline the request but, rather, that he’d done so many projects in the interim that the experience of doing Circus might not have been one that had stuck with him.

I needn’t have worried. All I had to do was wind him up and let him go.

How did you first find your way into Circus? Was it an audition situation, or was it pitched to you specifically?

Kevin notified my agent and said that he wanted to make an offer and that he wanted to meet me, and if we got along, he would solidify that offer and make it for real. I remember meeting—we talked and we got along really well—and he said, “Do you want to do it?” And I said, “Sure, I want to do it!” I mean, it sounded great. Who wouldn’t want to do it? A uniquely appointed show with Roger Rees as a drunken clown…? I mean, come on! [Laughs.]

By the way, Kevin wanted me to make sure to tell you that he said “hello.”

Oh, okay! That’s great. Yeah, Kevin was great to work with. I enjoyed working with Kevin. He was terrific.

He said that there seemed to be tremendous enthusiasm amongst pretty much everyone who was actually working on the show.

Oh, yeah, everybody was enjoying it! It was such a different vibe for a Hollywood sitcom. It was a really different feeling, and there was just so much excitement and movement with the circus people—real circus people!—on the set, moving in and out all the time. And the way they had the set built, with the big top, it was like a real circus. It was a great feeling. And I was having fun. As the ringmaster, I got to wear the red uniform and the boots and the hat and the whip and go, “LADIES AND GENTLEMEN!” [Laughs.]

So, yeah, it was really fun, and it was really quite an experience. I mean, the whole creation by Kevin was kind of outstanding because of its subject matter. A drunken clown, a gay strongman, and all the other circus types… And it was a family circus, and I was the older ringmaster of the circus. But what really made it interesting was the way in which the series—which, as far as I know, not even the pilot was even shown—was canceled by FOX in the middle of the day. At a meeting, the network guys had gone after Kevin, and Kevin…I forget what he called ‘em, but it was “fuckheads” or “stupid assholes” or some combination or other. Something like that. And an hour or so later, we were told to clear out. So we were basically thrown off the lot, in effect.

Now, the network certainly had some legitimate questions. These came up during the time when we filmed the episodes that we completed, and they had to do with the makeup of the clowns. This was an important factor in the network’s decision, because…I don’t think anybody, including Kevin as he created an outline for the future of the show, quite thought this far ahead. If it’s gonna be about clowns—not just Roger, the central clown—and it’s gonna be even a little bit authentic, you do have to have some clowns that aren’t just window dressing, that have to really participate in the story. That means you have to have a couple of clowns who are probably regulars on the show. And then you do have to have some window dressing, maybe some guys who show up every couple of weeks, and maybe some others who are just around in the background, performing some clown stuff or whatever.

But the problem, apart from the budgetary considerations vis-à-vis the number of cast, was also makeup. This is what I think nobody had really considered, and this proved to be a big point. If you have, like, eight or nine clowns, a couple of whom may be regular or semi-regulars and a couple of whom are actual clowns, and you do makeup on them, you’re talking about very elaborate artistic makeup for 10 or 12 or 14 people…and that’s in addition to the regular makeup for the rest of the cast that you’d normally have. Nobody has a makeup staff on a regular weekly basis big enough to do that kind of special makeup also. So it meant that they had to hire…I remember them bringing in five or six or seven special makeup people whenever we had a lot of clownage on the show.

Okay, so that’s bad enough from the network’s point of view, the added cost, but here’s where things really got tough. This was filmed, like many sitcoms, in front of a live audience. So if the clowns were integrated into the story, then you’d have a scene where the clown are doing clown stuff, but then you might have a scene where the guys are, like, y’know, at home or dealing with their families or just hanging around, and they wouldn’t be in either clown attire or makeup. They’d just be people. Part of the charm of the story, though, was that we got to see these people both backstage and onstage, and it was clear that if it was going to be a series, then the center of it could not be the onstage performance under the big top. The center really had to be the day to day life, and what that life was like, and the rigors of meeting deadlines for performances and so forth from a comedic standpoint, and that’s where Kevin wanted to go with it.

But when we would have our filming days, if you had a scene…well, the show nearly always opened with some clown stuff or circus stuff, actual circus acts, but at the end of the opening scene, the clowns were required to come back just as regular people a scene or so later, so all that makeup had to come off. Well, not only is clown makeup hard and lengthy to get on, it’s almost as hard to get off and to make your skin look normal again. And then you might have to come back in later in the show with the makeup back on again! What this meant for live audiences on taping day…well, a couple of times I know that we were there until four or five in the morning, with delays between scenes of sometimes, like, an hour in length, because of getting 14 clowns all made up again, and so on and so forth. So I’m sure the network has got to be looking at this and going, “What the hell have we done?” [Laughs.]

And there was the other thing about doing a circus series, which is that you do have to have circus acts up there, and, well, you can’t just go out and have a casting call for someone who can do the Uncle Sam thing on the eight-foot stilts, y’know? [Laughs.] You’ve got to have a real circus guy that does that! If you’re gonna have someone ride one of those velocipedes that are 12 feet high, that’s a special skill. There’s probably only two guys in L.A. that could do that…and they don’t cheap! And if they had real snakes, then they had to hire someone with real snake experience, and so on. For the budget, they’re negotiating with circus people, not actors. So from the network standpoint, this thing, they must’ve been looking down the road and thinking…

Oh! Another part of Kevin’s concept, to add to the novelty of it and the uniqueness of it… I don’t know if you remember an old series called Route 66, but at some point in their history, they were doing their shows from some of the cities along the old Route 66 to add further interest and novelty and authenticity to it. So Kevin envisioned at a certain point, since this was a traveling family circus, that maybe we could do different shows from different cities. For real! So, y’know, we’d be in Chicago today, St. Louis next week, somewhere in Texas the week after, and so on. So as the network looked at all this, they must’ve thought, “Boy, this show would have to be such a huge hit to justify or equalize these costs.”

Look, whatever Kevin said to them that insulted them, I’m sure they’d heard worse. I’m sure they jumped on that and said, “Okay, he insulted us, this is our way out,” because over the years of network/producer relationships, I’m sure that Kevin’s was probably not the worst they’d heard. They were just anxious to get out of it, I think…and once they did, they didn’t waste any time getting us out of it, either! [Laughs.]

Do you remember your reaction when you heard…well, first of all, when you heard that it had been canceled, but then when you heard more or less why it had been canceled?

Well, we were all disappointed in our various ways, but I think we all understood that even if the pilot had gotten on the air, even if there was somebody out there who sort of wanted to see this show in America, I think we all realized that there were impediments to any kind of long-term success, because you could see the costs. I mean, they were right there, plain as day. Could anybody sustain the cost of a show like this? Especially given Kevin’s larger dream, which was to have a traveling circus that really traveled. [Laughs.] Because if we didn’t travel…

I mean, that was part of the idea of it. How many circuses do you know that are permanent? So it almost had to be a traveling circus, and that meant there had to be significant changes in the set, as far as how the set was configured and the locale in which we lived when we were not onstage performing in the circus. So just the cost of that alone…well, again, somebody at FOX must’ve said, “So how do we do this? How do we show a different city every week using the same two stages at FOX that we’ve got now? What do we do?” And I can just see everybody saying, “You know, I don’t know if we can do this!”

Now, I can’t remember if we were originally contracted for 11 or 13 episodes, but I do remember that there was some difficulty in getting paid afterwards. We did ultimately get paid, but… [Hesitates] Do you remember what year that was?

That was 1992.

1992? Okay, well, in 1992, FOX was still operating in the loophole that said that they were not a network. They were allowed to get away with a lot of stuff by pretending that…and I mean really pretending, because it was just a fake. But they found a loophole in there in terms of language, and they exploited it, of course, because it was to their advantage to not be a network. So they were a network in everything they wanted to be a network in, but in those areas that allowed them to get away with stuff, then they would say, “But we’re not really a network!” And one of the important areas there had to do with pay and how the contracts were drawn up, and whether or not they had to do pay pension and welfare for the actors the same way that the Screen Actors Guild expects people who are signatories to the Guild stuff for actual networks to have to pay.

Now, the upshot of this was that FOX thought they had a legal claim to not having to pay any more than through the fifth episode, which would leave all of us with, like, seven episodes yet to be paid, which was quite a bit of money for all of us…and for FOX, too, I’m sure, not that they would have any trouble coming up with that. But then there was a larger question—and this was not resolved in our favor—and that had to do with pension and welfare. And by the way, that series was non-SAG. The way that series was set up, it would’ve been AFTRA had they been a network…or, rather, had they confessed that they really were a network, even though they were pretending not to be. That meant that any of the work that any of us did there did not go toward our AFTRA pension fund. Now, that’s significant, because for each actor…or the regulars, anyway…we’re talking hundreds of thousands of dollars that never went into actors’ pension funds.

I think all of us who worked on the show eventually got paid our salary, but it wasn’t easy. It took several months, and…I don’t know if it actually got litigated. I don’t think it did. I think it was just back and forth, back and forth, FOX trying to weasel out, and eventually they realized that they weren’t going to be able to weasel out without a long legal battle or a public relations battle that might make them look like the jerks they really were. [Laughs.] But the main question was whether or not we’d get credit in our pension and welfare…and we didn’t. And that really is significant. Everybody took that hit, including me, and everybody has that much less. Whatever the amount they made for those 13 shows, that amount of money will never show up as part of their pension. Now, that would mean that some people will never get an AFTRA pension benefit, maybe. That may have been the margin for many of them, and so on. FOX got away with something there.

But they were getting away right from the beginning. I remember when the first contracts came. I think we were all kind of shocked. The wording, the whole approach was very different from what we were used to from the three major networks. The form was different, the paper was different, the wording was different, the guarantees were almost nonexistent… So, anyway, it was a notable part of that experience!

Post-Script:

Long after this piece was originally written, I learned through the magic of Twitter that writer/director/script consultant Rich Nathanson had a copy of one of the episodes of Circus…and, even better, he was willing to digitize it so that I - and anyone else who might be interested - could finally see what Kevin’s series was actually like. I can’t thank him enough.