Random Reminiscing: Looking Back at My Many Random Roles Interviews (Part 27 of Quite a Few)

Featuring anecdotes from Skeet Ulrich, David Warner, Dee Wallace, Bruce Dern, Jim Beaver, and Elvis Costello

Back in 2021, when I celebrated the 10th anniversary of my first Random Roles, I was feeling a tad nostalgic, so I decided that I wanted to start looking back at my contributions to this A.V. Club feature, since it’s the portion of my freelance career of which I’m most proud.

If you accidentally missed the previous part of this reminiscing (and you may have, because it was in 2021!), you can check it out by clicking right here…and if you missed the part before that, well, each installment has a link to the previous installment in the intro, so just keep on clicking back until you’ve read ‘em all!

If you’re all up to date, though, then for heaven’s sake, why are you wasting time wiht this intro? Just dive right in!

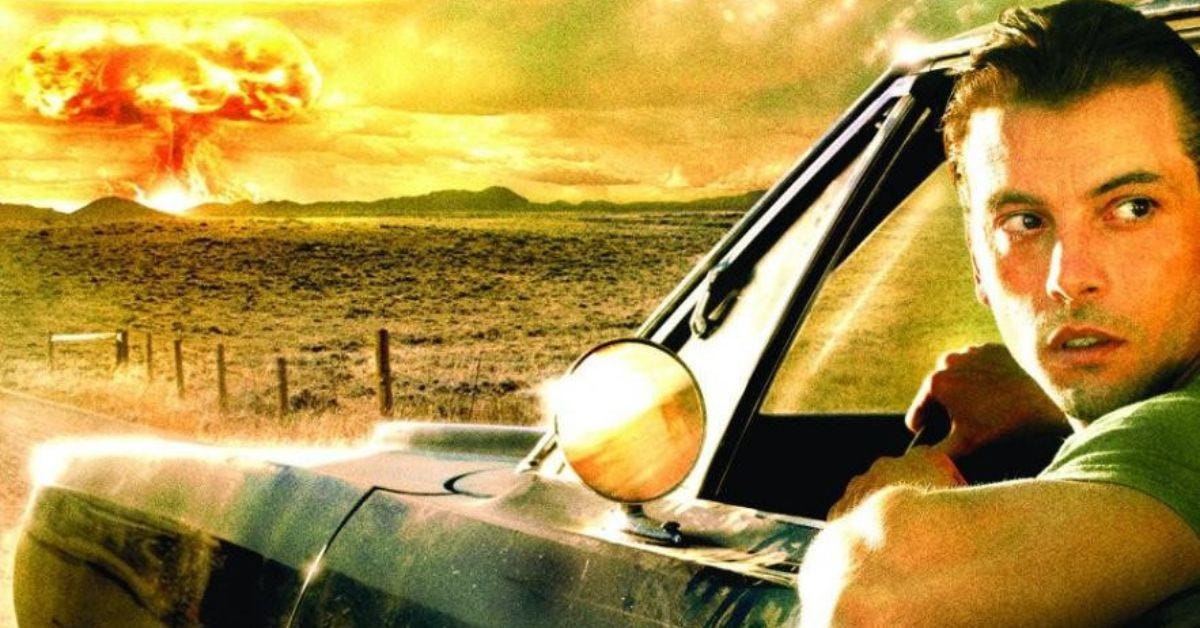

Skeet Ulrich:

Jericho (2006-2008)—“Jake Green”

Skeet Ulrich: That series was just so compelling. I’ll never forget: It was right around the fourth episode, maybe, when we see the missiles launched across the sky, and North Korea was testing missiles two days prior to that. Now it’s nothing new, but at the time it was kind of unheard of. Kim Jong-il didn’t test that many, so the timing involved was really eerie.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t a show that was a CBS-type show. Now they have their summer miniseries that are sort of similar to it, but they had never really stepped outside of cops and lawyers and doctors, and they were scared of it. Lennie [James] and I spent a couple of hours every night rewriting it, and fortunately we were all on the same page: the producers and Carol Barbee, Lennie and I, and really, the whole cast.

I’ve done a lot of stuff in my career, and you hope you make friends while you’re doing things, and you hope you’ll keep in touch with a lot of people, but the way careers go, one person goes this way, another goes that way, and it’s hard to keep in touch. In fact, Alicia [Coppola’s] husband was over here yesterday. We talk, all of us, all the time. Tim Omundson just recently suffered a stroke, and producers and actors and everybody were showing up at the hospital and showing up at his house. That became a real family, that group of people, and I think it was felt from an audience perspective. You could feel that connection somehow. But plotwise it was just a really interesting notion of what this world could become and what do we do if it does?

We were close [to a third season] about four or five years ago. Karim Zreik, one of the producers, called me and said, “Netflix has a schedule, they have budget, they have locations. Are you in?” I said, “Absolutely, with one proviso: That first script back has to time-jump five years, and the world has devolved way lower than we could ever have imagined.” And they were on board with it. And CBS wouldn’t sell it. The deal wouldn’t work for them.

I didn’t realize it had gotten that close. That sucks.

It’s so frustrating. Because the thing that killed that show was the marketing strategy that they had for it. Lost was in its fourth season when they split it into basically two 11-episode half-seasons, with a three-month hiatus in between the 11th and 12th episodes. But they had four seasons, and they had a following, and they did a massive amount of marketing when they broke between the 11th and 12th to let people know when it was coming back. And CBS wanted to use that model of marketing for Jericho. And it killed it.

I mean, we had a big fan base, but they didn’t do the marketing to let people know when it came back, and then when the numbers dropped, they blamed us. So it was really frustrating. I think, because we were such a family unit, we all wanted to come back and do those seven episodes [for a second season], but we were bitter about it. I mean, they cut our budget in half to do those seven. Our D.P. and most of the people that’d helped tell that story had gone off to other jobs. We typically shoot an episode in eight working days, and they made us do it in seven. So they brought us back, but they didn’t. It left a bad taste in my mouth, that whole experience. It seems like every series I’ve been a part of, there’s been some sort of frustration, business-wise.

David Warner:

The Ballad Of Cable Hogue (1970)—“Joshua”

Straw Dogs (1971)—“Henry Niles” (uncredited)

Cross Of Iron (1977)—“Hauptmann Kiesel”

David Warner: Ah, yes, The Ballad Of Cable Hogue. Well, that was my first film I did with Sam Peckinpah. You know, I did three films with Sam: The Ballad Of Cable Hogue, Straw Dogs, and Cross Of Iron.

What did you think of Peckinpah when you first met him?

Well, I’ll backtrack a little bit to start, because Peckinpah has a reputation. But I think you know that. [Laughs.] Well, if you work with somebody three times, that reputation doesn’t matter, if you understand. If you can’t stand each other, you don’t want to work with each other again. We were fortunate that we got on very well, even though we were totally different personalities. But, yeah, The Ballad Of Cable Hogue was my first invitation to go the United States. Do you know the film director Sidney Lumet?

Absolutely.

Well, I worked with Sidney, and I got a phone call one day from Sidney, and it wasn’t a usual occurrence that he would call me from New York to London. But he said, “Listen, you’re going to get a phone call from a man you’ve never heard of called Sam Peckinpah. I’ve just seen a reel of his latest movie, and I urge you to work with him.” I said, “Oh! Okay.” So Sidney got off the phone, and half an hour later Peckinpah calls from wherever he is in the United States, introducing himself, and asks me if it would be okay to send me a script. I read the part, and I thought, “Oh, this is great!” It was a Western, and it was with the great Jason Robards… And what an experience to go out to America! And some friends showed me some early Peckinpah movies. This was before The Wild Bunch came out, you see, so he wasn’t quite so well known. So, anyway, I said to my agent, “I’ll do it!”

The day before I was due to fly to Los Angeles, I had a panic attack and said to my agent, “I can’t go. I can’t fly.” He said, “You know you’ll lose the part, don’t you?” I said, “Yes, I don’t care. I don’t care! I can’t fly!” He said, “Okay, I’ll let them know.” So an hour later my agent calls me back. He says, “Okay, this is what you’re going to do. You’re going to get on a train at Victoria Station in London. You’re going to go down to Barcelona in Spain. You’re going to stay the night in Barcelona. You’re going to catch a ship that’s gonna take two weeks to get to New York. You’re going to get on a train from New York to Chicago. You’re going to then go across the United States to Los Angeles. A car will pick you up and take you to near Las Vegas. And they’ll be waiting for you.” I said, “That’ll take about three weeks!” He said, “Yes! They’re going to wait for you!” I said, “What?” [Laughs.]

So this is what happened, and what I’m trying to tell you is this: with all his reputation, Sam Peckinpah had arranged to wait for an English actor that nobody had ever heard of to get himself to the desert. I couldn’t fly, and it took me all that time to get to him, and when I got to this little motel in Echo Bay Resort in Nevada, I went straight to the bar, where I was told that Sam was waiting. And he said, “Welcome to the club!” Which I think meant that he didn’t enjoy flying, either. Anyway, that was my first meeting with Sam Peckinpah. That just shows the kind of guy he was. I immediately felt so at home.

It was a difficult shoot, because it was in the desert, and it was a total culture shock for me, and it was the whole wild experience. But to meet Sam for the first time and then to get to know the great Jason Robards was something that I’ll never forget. How’s that? [Laughs.]

That’s amazing. So your next film for Peckinpah was Straw Dogs, but you aren’t actually credited in the film.

No, I’m not. You want to know the story about that, don’t you? First of all, about three months before Sam asked me to do Straw Dogs, I had an accident. I won’t go into details about it, but I smashed both my feet and was in hospital, and I had a 50/50 chance of whether I’d walk again. And Sam didn’t really know too much about what was going on, but he offered me a part in Straw Dogs, and I said, “Sam, thank you, but I don’t know if I’m going to be able to get up and walk,” and I explained that I’d had an accident. And he said, “You’ll get up and walk.” [Laughs.] I said, “Oh, okay, if you’re the director, I will!” Anyway, I was able to hobble. If you see the film, I’m on sticks and I have a limp and can’t walk properly. Well, that wasn’t acting, that was real. And as a result of this accident, it was difficult for me to be insured for the movie. So Sam told me this, and he said, “Listen, I know you promised you’ll be okay, but they won’t insure you. But I’ll cover you, and I’ll cover the production, if anything happens.” That was a gesture of loyalty and friendship, I can tell you. First he waited for me for three weeks without knowing me, and now here he is saying that he’ll pay the insurance if anything goes wrong. That’s not bad!

But you wanted to know about the billing. What happened, evidently, was my agent thought that, having done a film called Morgan! and a couple of other movies, I was worth having my billing of the same size as Dustin Hoffman and Susan George. And that was rejected by their agents. But that’s the way that show business works. So I said, “Oh, to hell with it! I want to do the movie. Don’t have me on the credits at all. Don’t have me anywhere. Let’s not fight over it. Just ignore it.” And that was suggested to Sam, and he said, “Oh, that’s a great idea!” [Laughs.] A few critics over here hated the picture so much that they said, “Well, no wonder David Warner had his name taken off the credits.” But, of course, that isn’t true. My name isn’t even on the cast list. Even though you know I’m in it, it’s not officially on the cast list. So that’s the story of that one.

We might as well wrap up the Peckinpah trifecta and touch on Cross Of Iron, which flew under the radar at the time but has since become rather well-respected.

I believe it has. I read a quote that it was one of Orson Welles’ favorite war films. Again, it was great to have been asked to work for Sam for a third time. I was a Brit in his repertory company. Because he used the same actors a lot. It was a great privilege. As I said, he had a reputation, but as far as I was concerned, there was a genuine feeling of brotherhood and affection there.

Did you continue to stay in touch with him after that film?

I did, indeed. Whenever he came to England, he got in touch, and a few times after we’d finished filming, when I was in L.A., we’d meet up occasionally. But his health started to deteriorate, you know, so I didn’t see all that much of him. But he’s one of the very few directors I kept in touch with after filming was finished.

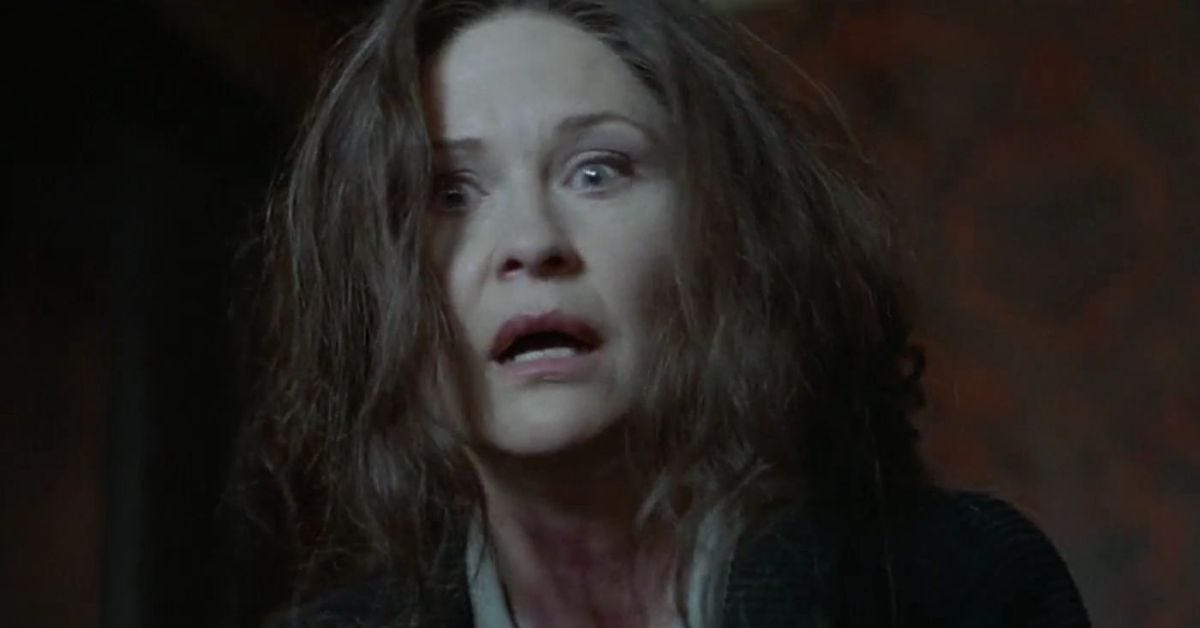

Dee Wallace:

The Frighteners (1996)—“Patricia Ann Bradley”

Dee Wallace: I could talk for an hour on that one. Well, I had to audition at Universal, and I just remember thinking, “I’ve got to go all the way, I’ve got to go all the way.” And when I went in and met Peter Jackson, I was such a huge fan of Heavenly Creatures, and I said, “Peter, just, please don’t see me with this blond hair, okay? See me with long, black hair or something. But this is not how I see Patricia.” So I auditioned and got the part, and then Michael [J. Fox] came in and watched it. He and I had met a year earlier, just in passing, so he signed off on me, and we were off to New Zealand.

We got down there, and the night before we were supposed to start shooting, Peter came over and said, “You know, Dee, we’ve decided to rewrite the script.” I said, “What?!” “Yes, so we were wondering, would it be okay if we sent you, your nanny, and your daughter on a trip through Queensland? We’ll just send you on this trip for two weeks, and we’ll have a guide for you.” I said, “Okay, well, let me think for about two seconds. Okay!”

The Frighteners was such an interesting experience in my life. I don’t know how many of your readers know that my husband died in the middle of it. Well, he had a heart attack, a severe heart attack. They flew me back, they did an angioplasty, he appeared to be fine, and he said, “Look, go back. They’re holding filming for you.” He was an actor, too. So I flew back. Four days later, he passed away from a blood clot. I flew back again, put his service on, picked up my nanny and daughter, and… [Sighs.] I flew four times across half the world in two weeks. Seriously, I didn’t know where my body was for a couple of days. But it’s some of the best work and rawest work I’ve ever done. I adore Peter Jackson, and I love that part. Talk about everything I love to do everything as an actress, playing that huge arc from Patricia the victim to Patricia the freaked-out murderer.

I remember when we were in wardrobe and makeup, discussing the difference between when Johnny comes in and takes me over and how to age me. I looked at Fran [Walsh], Peter’s wife, and I said, “Oh, no, I think I get younger. I think I’m back in what excites me. I’m back in my element.” And she looked at me like, “Oh, my god, what a great idea!” So that’s what we did. Actually, in a very strange way, it worked physically, because when Chris died, I went through so much grief and everything that I lost about 15 pounds, and that kind of coordinated with the time I was going back into the demonic Patricia.

I don’t know, I look at that part, and I go, “I don’t know where it all came from,” but between me and Peter and Patricia, it was quite a ride. And I will love Peter Jackson and everybody on that crew with a full heart until the day I die. When I got back there, everybody came around to hold me up and to take care of my little girl. They played foursquare with her. They actually built a little flying apparatus, because she was with me when I went to try out my flying stuff, and she said, “Mommy, I want to fly like Peter Pan!” So they built her a little one so she could go up, too. And at the end, I went in to settle up my money, because they said, “Look, we’ll take care of doing everything, you just go take care of whatever you have to take care of, and you can settle up at the end of this,” so I figured I was probably going to owe them money by that time, going four times across the air with three people. But I got there to settle, and the bookkeeper said, “No, this is Peter’s gift to you: We’re just going to take care of all of that.”

That’s really nice.

Everything during The Frighteners was so humane and respectful, down to the best boy on the set. It was a grand experience of my youth.

Bruce Dern:

The Cowboys (1972)—“Long Hair”

Bruce Dern: One of the neat things about my career has been the people I’ve gotten to work with. My generation was extremely lucky, because when we came to Hollywood, we still had a chance to work with the legends. We’re not legends today. You can’t be a legend today. Everybody knows what you do after school. There’s no secrecy after school. But what people forget is that—regardless of acting ability—those people were bigger than life, and that’s because we didn’t know anything about them except the characters they were playing.

I was lucky enough to work with John Wayne a couple of times, Kirk Douglas a couple of times, Robert Mitchum, Bette Davis, Olivia De Havilland… Just a whole bunch of ’em. And I found—and I think Nicholson found the same thing—that everyone encouraged me again and again to push the envelope and go out on the edge. I liked that.

I remember the day I shot John Wayne in The Cowboys. He had never had a bullet hit put on him. Never! And he leaned into me and said [Doing a John Wayne impression.] “Is this gonna hurt?” And I said, “Absolutely it’s gonna hurt! You should get one of those big USC Marching Band Roman shields that you put on the front of you, ’cause they’re gonna blow a hole in your chest!” And he knew that, but he’d never had it done. Mark Rydell was the director, and we decided that the only way the scene could really work for an audience is if Wayne was surprised. So unbeknownst to him, we put a bullet hit in the back of his jacket. And I shot him in the back the first shot. And he did not know that was gonna happen. He played it like a pro, went all the way through it and everything, got up, and told Mark Rydell and I we were both pricks. [Laughs.]

Oh, and just before we did the shot, he said, “Oh, they’re gonna hate you for this.” I said, “Maybe. But in Berkeley, I’m a fucking hero!” He got a big kick out of it, because he’d just done the Playboy interview. They did a big, long interview with him where he kind of ripped America a new butthole unless they lived on Balboa Island, where he and the rest of the boat people lived.

But [John Wayne] was just great to me. He did something to me that was the most welcoming, inviting thing in my career. He said to me on the first day, “I want you to do me a favor.” I said, “Yessir?” He said, “I want you to pick on me all day, every day, and be absolutely careless with your attitude toward me, so that these little kids that are scared shitless of me, if you can treat me like that, then what might you do to them?” And it worked! And had he not given me that blessing, so to speak, I’d have backed off a lot. But I didn’t.

Jim Beaver:

Gunsmoke: To the Last Man (1992)—“Deputy Willie Rudd”

Gunsmoke: The Long Ride (1993)—“Traveling Blacksmith”

Jim Beaver: I made two Gunsmoke movies, and they told me at the time that I was the first actor in Gunsmoke history to ever play different roles in two consecutive Gunsmokes. Of course, this was the TV movies, it wasn’t the series. The series had been off the air for a number of years.

First off, you’re doing a Western. There’s hardly anything more fun. And I had a couple of fun scenes. Deputy Rudd wasn’t clueless, but the job was a little bit bigger than he was. So when Marshall Matt Dillon rides in trailing three bodies on his pack horses, I found myself—as the character—intimidated and not exactly certain what to do.

It was an interesting situation. I found myself really excited to be there—I think we shot that one in Arizona, east of Tucson—and I was really excited to be doing a western and one as iconic as Gunsmoke, and I was… [Sighs.] I was really kind of disappointed when I met James Arness, because there wasn’t anything outgoing about him. He wasn’t especially friendly. He wasn’t mean or anything, but he was kind of terse, and he didn’t speak much directly to me even when we were rehearsing scenes. He would say to the director, “I’ll ride up, and then this guy will do this or that.” And I was “this guy.” I had one little vaguely cordial conversation with him about a mutual friend, but other than that, he wasn’t as warm and friendly as I had expected and sort of hoped. He managed a “hello” in the morning, but that was about it.

Also, I was taken aback a little bit because he would do one take or so, and then he would say, “That’s it, I’m done,” and he’d walk off, whether they’d gotten it or not. So I played an awful lot of my scenes with him to his stand-in. I remember I had one scene where he’s on horseback and I’m walking alongside him talking, and the double is on the horse, and the words are coming from the script supervisor, who’s behind the camera. So I’m walking along, having a conversation with someone I’m neither looking at nor hearing! Which was pretty weird.

I found out later that part of the reason was that Arness was badly wounded in the attack on Anzio in World War II, and his legs were shot up pretty bad, so he had a hard time standing. So they would shoot his stuff as quickly as possible so he could go get off his feet. And that was a lot of the reason why, with the coverage, I’d be acting with his stand-in. Once I understood that, I found it imminently forgivable. [Laughs.]

And what was particularly odd was that there were lines that were really kind of cool, and on a couple of occasions he said, ‘I’m not going to say that.” And the director said, “Well, we need to get this line out,” and he said, “Well, let this guy say it,” meaning me. I ended up with a couple of really great laughs in the movie because he didn’t want to say these lines that turned out to be pretty funny. But I left the film thinking, “Well, this guy’s kind of a sourpuss and not very warm and friendly,” and it was kind of a disappointing experience. But then I went to a screening of the film a month or so later, and those lines got big laughs, and he came up to me afterwards and said, “You really did well with those lines!” And I thought, “Well, that’s nice.”

A few months later, I got a call to come to New Mexico to shoot another one, doing a different part, this time a blacksmith. You would’ve thought I was Jim Arness’s long lost son. He was so cordial, so friendly. He was, like, “Oh, you did such good work on the last one, I’m really glad you’re back on this one.” I thought, “Okay, is this the good twin?” [Laughs.]

The only thing I can think of is that maybe there was something going on with him personally during that first one where his mind wasn’t on it and he wasn’t up to being happy-go-lucky with everybody. But he was just the sweetest when I worked with him the second time. Again, it was a fairly small role, just a couple of scenes, but he treated me really nice, and I had a lot of fun. Even on the first one, I had a lot of fun. Nothing beats playing cowboy.

Elvis Costello:

Two And A Half Men (2004)—himself

This is a must-ask, if only because of the disparate group of people you were there with. Sean Penn, Harry Dean Stanton…

Elvis Costello: And that other guy! I don’t even know who he was. I think he was Sean’s bookie. I don’t know who he was. Just a poker buddy of Sean’s, I guess. He must have a SAG card to be on the gig, though, right?

Sean was great. I kept giving him my guitar and saying, “Go and play the guitar.” And he said, “Nah, I don’t play the guitar.” I said, “Then what the fuck were you doing in Sweet And Lowdown, then?” That’s real acting: You learn to play like Django Reinhardt and then forget again. If I learned to play like Django Reinhardt, I’d fucking remember it.

But the best thing was Harry Dean, god rest his soul. I actually knew him already. We’d sung together a couple of times. I met him with T Bone Burnett, and he was great company to sing with, and we’d sung a couple of old Jimmy Reed songs or Hank Williams songs in a club. We’re all drinking iced tea that’s supposed to be whiskey, and he’s drinking real whiskey, and it’s nine in the morning! If you want to see hardcore, that’s him. It was pretty fantastic. And again, every take was different, and it was all great.

His silences were as important as his responses.

Well, yeah, that was his thing. But he covered a lot of ground. He went so far back, his career. I mean, when I say to people, “I was once on a TV show with Frank Capra,” they say, “You liar!” I say, “No, check it out: I was!” I was on a TV show with Count Basie as well.

I mean, these are not necessarily great moments in the overall sweep of what you do. My real job is writing songs. It used to be making records and playing shows. But these sort of asides, why would you not want to have the experience of being in the desert for three weeks with a bunch of drunk people, trying to make a fake Western? Have you ever actually seen Straight To Hell?

Most certainly.

Okay, because not many people have. Tell me, did Quentin Tarantino not rip off Samuel L. Jackson’s character [in Pulp Fiction] from Sy Richardson’s character in that movie?

There’s definitely an argument to be made there.

I mean, he totally just went CLIP! CLIP! and put it in there. It’s totally the blueprint! Not that Samuel L. couldn’t have done the role anyway, but the whole thing, it’s too inside. It’s too like it. The same way he looks, the same tastes, the same kind of menacing way. It’s still great, though. It’s like jazz. It’s like a great jazz player playing a whole solo, and then they suddenly play some quotation from another song. That’s how art works.