When It Comes to Finding Del Close Stories, My Interviews Are Not a Wasteland

Given his status as a legendary figure in the world of improv and how many times I’ve seen or heard his name cited as an influence, mentor, or teacher both in my interviews and those of other journalists, it still amuses me a little bit that my own introduction to Del Close didn’t come through comedy.

It came through a comic book.

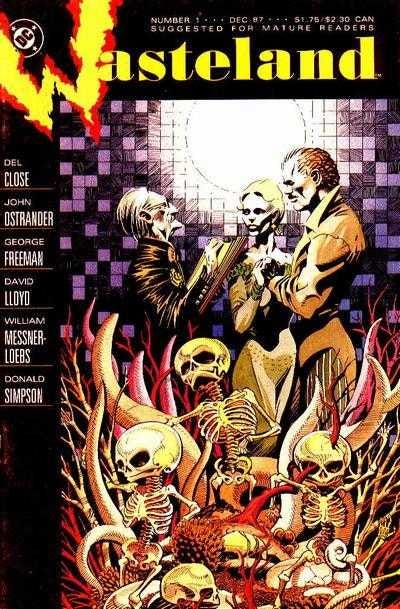

It feels like forever ago, but there was a time when I loved comic books more than music. This is not to say that I don’t still love comic books, but there was a turning point in 1989 - and I don’t want to say it was tied to DC Comics cancelling Wasteland, but if you want to kick up the drama, sure, let’s say it was - when I decided, “Screw this, I’m selling all of my comics and buying CDs instead.” I don’t totally regret this decision, because I know full well that my collection was not filled with expensive gems, but once in awhile I do think back and wish I had some of the comics I sold…and, yes, among those comics is Wasteland. It was a weird, creepy series that was somewhat reminiscent of DC’s House of Secrets and House of Mystery and those sorts of titles, but the material was deemed by the DC Powers That Be to be “for adult readers,” and that is absolutely a fair cop.

Given my fondness for both the series and Close’s comedic accomplishments, you can imagine that I was thrilled when I heard about this new documentary, For Madmen Only, which focused on both aspects of Close’s career. In addition, it served to remind me of how many Del Close stories I’ve accrued over the past several years, and I figured, “Say, why don’t I put them all in one place?” So I did.

Enjoy…and if you like what you read, I promise, it will not offend my artistic sensibilities if you decide to upgrade to a paid subscription!

You were in The Nervous Set, a Broadway show that first came across my radar by virtue of the fact that Del Close was in the cast.

Barry Primus: That’s right. It was written by Jay and Fran Landesman, who were these very important people during the ‘50s who ran a magazine called Neurotica, which was an advanced magazine for very hip writers. I think it was the first place where Jack Kerouac actually had anything published. But we were in St. Louis, and they had a nightclub there which was very famous – it was called the Crystal Palace – and they had people like Elaine May and Mike Nichols and Lenny Bruce playing there. All kinds of wonderful people. And we did a series of plays there. It was kind of like a cabaret, where you had dinner and watched plays, and they put together a musical called The Nervous Set. It was a wonderful musical. It didn’t last long. But the songs, some of them were classics, like “Spring Can Really Hang You Up the Most” and “All the Sad Young Men.” There were some wonderful songs, and it was a wonderful experience.

I think it was one of the first Broadway plays ever to have a jazz orchestra onstage. It was basically about the underground hippies or – as they were called in a book by Kerouac – Subterraneans, which were people who by day had regular jobs but at night became hippies, with the free love and drugs, and they were poets and writers. So they made this musical about a couple that were that and lived out in Scarsdale, and Del played a kind of crazy Allen Ginsburg character, and he was really wild and wonderful. And I played a Jack Kerouac character. And Del also was part of the Season with us. He was a terrifically far out guy and became very important because he trained all these wonderful people. I think he trained the Belushis, didn’t he?

Absolutely. And the Murrays.

Yeah, and people always talk about him. Apparently he became a real force. He became the guy who held the rules of how to improvise which became so popular all over and which influenced Saturday Night Live and all this new comedy.

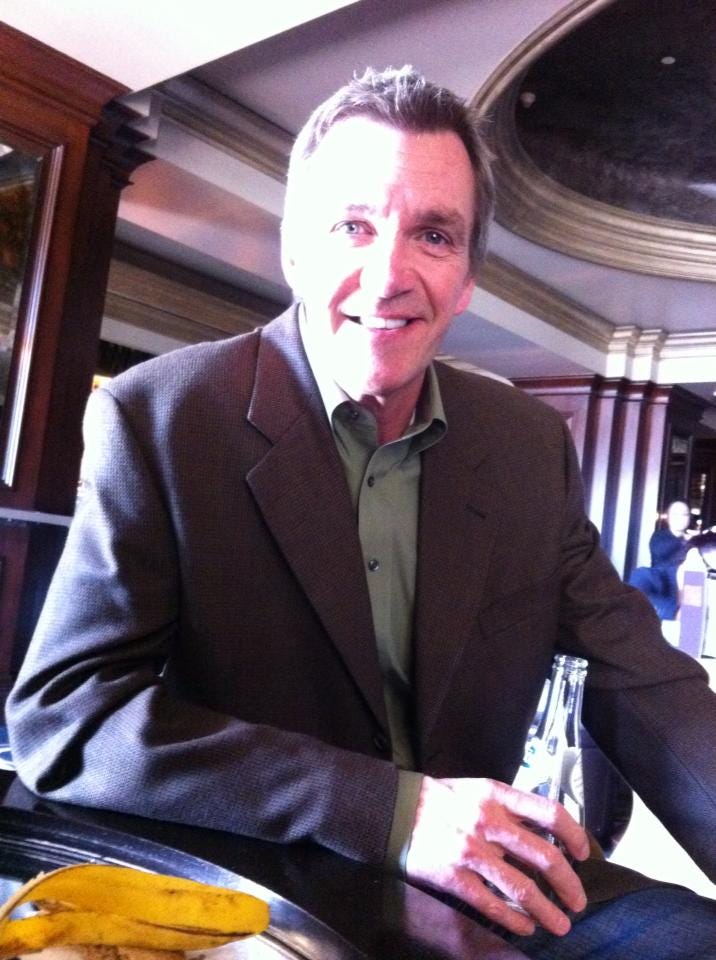

Let’s talk about some of your earlier credits, specifically your experiences working with Del Close.

Neil Flynn: Oh, yeah. [Hesitates.] How do you even know who that is?

Well, he is pretty legendary.

[Laughs.] Fair enough. Well, Del and I were both in a production of Hamlet in the mid-’80s with Chicago native Aidan Quinn starring as Hamlet. Del was Polonius, and that was pretty much his crowning glory, although he still had more than a decade left to live. In fact, I can’t be proven wrong by him now, so I’ll say that it was probably the thing that he was the most proud of. And rightfully so: He was excellent.

Who were you in the production?

Well, it’s nothing to brag about, although it was interesting. I played the non-existent part of the king’s bodyguard. It was sort of an updated version, so I was like a CIA sort of bodyguard for Claudius. I never spoke, but it was the best experience onstage I ever had in my life, because I spent almost a year just observing Hamlet being rehearsed and then performed. Not a lot of work, but a great experience nonetheless.

Anyway, Del and I knew each other from that, and I knew he had this improv theater, but that wasn’t my thing. I was Joe Dramatic Actor. Then I came out [to Hollywood] and didn’t find any success for about five or six years, so I moved back to Chicago, more or less starting over. And with nothing to do on a Wednesday night or whatever, I passed by this sign that said “ImprovOlympic,” and I remembered that. So I went in and saw the show, and I realized, “Oh, this is Del’s place!” And I ended up signing up, pretty much for a lack of nothing else better to do, and… as I’ve said before, it was probably the single best professional decision I ever made. Before the year was out, I was playing with the house team, having the best slot: Friday and Saturday night, every week. Those people went on to be the Upright Citizens Brigade. And Adam McKay, who’s now… [Smirks.] ...a somewhat successful writer-director.

That was 20 years ago, but you look at that group and we just happened to be… I suppose you could spread some credit around the performers, if you wanted to, but mostly I give the credit to chance. You had a bunch of people in the same place at the same time with the same interests and approximately the same skill level who knew each other better. Some went to Second City, some didn’t. But an alarming number of people from that short chunk of time ended up having success in TV or movies. Amy [Poehler], Tina [Fey], Horatio Sanz… And a number of people became writers. I mean, I’m not talking Tom Cruise-level fame or anything, but just the number of people who’ve gone on to successful careers in comedy? It’s not a very common thing.

That was the most important chunk of time in my professional career, even though… Let’s just say that if you remove making money from your definition of success, then those were my most successful years. Building those friendships and getting that experience. Because before that, I’d never done anything funny. I’d never really even tried to be funny.

You were working at places like the Goodman and Steppenwolf theaters, right?

Yeah, and Galileo with Brian Dennehy was not the laugh riot of the season. [Laughs.] But the acting business is so difficult that it’s never a bad idea to develop another side to your abilities. It’s like learning to switch-hit or something. Carry a catcher’s mitt and a first baseman’s glove, ’cause you never know which one you might need. It was a good idea that I tried it, and it was good fortune that it turned out that I could play comedy. Not that I didn’t think I could. I mean, I’d done it in my life. I just wasn’t considering it in my career. But it turned out that that’s the door that opened, and I feel very lucky.

And you still keep your improv chops up, with your own group in L.A. called Beer Shark Mice.

Actually, we did a show a few weeks ago, which was our first one in a couple of years, I think. It was fun. It’s always great to get up with those guys. And I feel very lucky to have been on Scrubs and now The Middle, and in a different sense I feel proud to have been part of that family in Chicago and also Beer Shark Mice, both of which have been influential in their way, for people who were witnessing it with an interest toward doing it themselves. Like students who were seeing what was possible with practice and experience. For some people, that means something. And I’m glad to have done that.

To bring it back to Del Close again before shifting gears, how valuable is his “Harold” method of improv to what you do now with Beer Shark Mice?

Um… if I tried to do “Harold” now, I would fail at it. [Laughs.] It’s been a very long time. I haven’t done a “Harold” in so long. What it is… even though it’s a perfectly legitimate form of improv, it’s a little bit of a starter’s form. Because it gives you a structure that you can hang onto rather than just a wide-open space to do whatever you want in. It exists because it was the first—as far as I know—long-form improv structure. There was no such thing before that. You couldn’t just, say, improv for 45 minutes. It didn’t make any sense. There was no way to do it. So they put in this structure so it could be done, and so the performers wouldn’t get lost. That’s my thinking on it, anyway. So even though it’s an absolutely legitimate form, it’s possible to take those training wheels off, if you will, and just go freeform for 45 minutes or an hour. People have gotten so much better at long-form improv that it’s no longer necessary to have those rules.

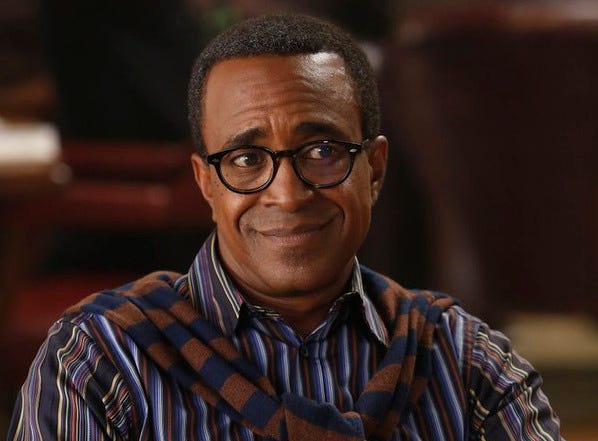

Given that you worked at ImprovOlympic and Second City, did you have any close encounters with Del Close?

Tim Meadows: Yeah! Del was one of my teachers!

Do you have a scary Del Close story? It seems like everyone has a story about how he terrified them, as well as one where he taught them a valuable lesson.

I have a combination, one where he was scary but which is also an example of what a great man he was. He did this show called “Honor Finnegan Saves the Universe,” and it was performed at the ImprovOlympic, and he told Charna Halpern that he wanted certain actors to be at this rehearsal, and she told me that I was one of them. So I was sitting in the rehearsal with all these other people, and then he looked around the room and he said, “What are you doing here?” Talking to me. And I go, “Oh, they told me I was supposed to be here.” He said, “No! Get out of here! You’re not supposed to be in here!” And I got up and I left the room, and I was really embarrassed. Nobody said anything.

A couple of days later, I was at the bar, I’d just done a Harold and it was really good, and Del came up to me, and he goes, “Look, I didn’t want you in this show because I don’t really have anything for you, but the next show I direct, I want you to be in it.” And I said, “Oh, okay. Thanks, Del!” And he barely ever talked to me! But the next show he directed was for Second City, and I was in the touring company, but when he took the job as the director, he told them he was only going to take it if he could hire the cast that he wanted for his main-stage cast…and it was me, Chris Farley, David Pasquesi, Joel Murray, Joe Liss, Holly Wortell and Judy Scott. Those people were the people he picked to be in this cast.

So he kept his promise to me: he said, “The next show I direct, I want to hire you for,” and that was the next show he directed. So he changed my whole fucking career based on that…and it all started with him yelling at me to get out. [Laughs.] The last time I talked to him, I reminded him of that story, and we both started crying. I was talking to him on the phone, and we just started crying. I told him, “Del, I’ll never forget what you’ve done for me. You changed my life in more ways than one.” He was great.

You mentioned having done a Harold. When I interviewed Neil Flynn — another of Del’s former cohorts — I asked him if he could still do a good Harold, and he looked vaguely horrified at the thought. Could you still pull off a Harold if pressed?

Yeah. I could, yeah. I mean, I still improvise, though, so I’m not… I’m a little rusty, but not that rusty. My big problem is going from stand-up to improv, because they’re such different parts of the brain that it can be a little difficult. But, yeah, I could still do a Harold.

Joel Murray: When I went to Loyola Rome, I hooked up with my good friend Dave Pasquesi on the flight there. I was sitting next to a guy who had a guitar between his knees, and I ended up going to the back of the plane and talking to the stewardess and talking to this guy who turned out to be Pasquesi. Back then, the flight was, like, 14 hours or something crazy, and we just kept drinking beer until the stewardess at one point said, “There’s no more beer. You’ve drank all the beer on the plane.” So we decided to go to cognac, I think. But Pasquesi and I were in the Second City together, we did some talent shows, and we actually kind of panhandled and did bits in Rome, trying to get money. He used to juggle and I’d sing.

And then when we got back, a friend of mine said, “We’ve got to go to this class with Del Close,” who was kind of an improv guru that taught Belushi and Aykroyd, Gilda Radner and all those folks from Saturday Night Live as well. So we went to a class at Del’s, and Pasquesi and I went up and did a scene, and he was very happy with it. And he said, “You know, your brothers have been very good to me over the years, Joel. I’m going to give you a scholarship.” [Hesitates.] “But, you know, I really like that Pasquesi, so what do you say I give you both a half-scholarship?” So I went from having a full ride to improv classes to a half-ride. But Dave and I stuck together from then on, and we were eventually on the main stage at Second City together, so that was pretty cool.

Tim Meadows told me about his origins with Del and how he ended up in that main cast with you and Pasquesi.

Yeah, well, we kind of got Del to come back. We had a coup. We were kind of young turks that got him back, to work with us and all the Del-lites: Chris Farley, Meadows, myself, Pasquesi, Joe Liss, Judy Scott, and Holly Wortell. It was really a fun time.

Supposedly, when you were first offered the role of Jame Gumb in The Silence Of The Lambs, you actually called Del Close in Chicago to ask him what he thought about you taking it.

Ted Levine: I did! Wow. Wow! Yeah, I’ll tell you why that happened. I had gotten the part and went to New York for a read-through, and this was one of those ones where everybody was pulling their weight, and everyone was there at the read-through. All of these departments were there. And Locations was there, and they came up to me with a pile of Polaroid photographs—we used Polaroid photographs in those days—to show me these locations that they were considering for the Jame Gumb house. And I’m flipping through these pictures of houses… and the hair on the back of my neck started rising up. And I said, “Where the hell… Where are these houses? Where is this?” And he goes, “Well, we found this really depressed little coal-mining town on the Ohio River.” And I said, “Bellaire, Ohio?” He said, “Yeah!”

Now, Bellaire is where I was born and lived until I was 11 years old… and the house they were looking at for the Gumb house was the haunted house next to my little girlfriend’s house, where would go for lunch because my mom, being a physician, worked. And this house was this scary house next door to Megan’s house, down by the river. They’ve all been bulldozed now for a stupid highway, but this house… They didn’t end up using it. They used a house a few doors down. But Belvedere, Ohio, where Jame Gumb allegedly lived, was actually Bellaire, Ohio, where I was born and raised.

So it freaked me out… and I didn’t know what to do! And I knew that Del was a warlock-y, black-magic kind of guy, and since I was kind of freaked out and Del was a bit of a friend, I called him up. And he said, “Oh, it’s a wonderful thing!” He was all happy about it. And I said, “Okay, good.” So I guess it turned out to be a wonderful thing. But maybe I sold my soul at the time. I don’t know.

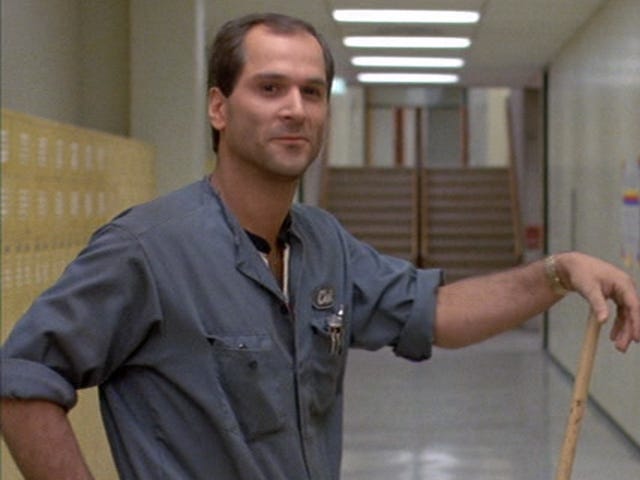

If IMDB can be trusted, your first credited appearance on camera was in the lofty role of Mechanic #3 in Michael Mann’s Thief.

John Kapelos: Well, I mean, that’s if you want to go by IMDB. Mechanic #3… I was up for Mechanic #2, but I didn’t get it. [Laughs.] No, but that was an inauspicious start. Michael Mann, who I like, and I was working with Del Close in that, if you know who he is. The guru of improv. We were doing something called “The Numbers,” which was a prison game where we were sort going, “Your mama’s so fat…” I didn’t know what the hell this game was, but I was trying to play it, and they’re trying to get me to do it, and we were shooting this sequence, and I’ve got to say, when they started rolling the camera, I could barely speak. I was so nervous.

How did you end up at Second City? Did you just have the idea to audition, or did someone suggest it to you?

I was in the University Of Ottawa and saw the road company of Second City, and I really fell in love with that. And then the next day, I fell down some stairs and broke my arm and ended up dropping out of university, hitchhiking to the west coast of Canada, and working on an oil rig for about eight months. I sort of had a falling-out with my family—I was rebellious—and I ended up working at a record store, pricing albums. I remember pricing Steve Martin’s Let’s Get Small—like, thousands of them—in this shop in Vancouver, and I had a crummy little apartment. It was a bad time. Fun adventures, but also sort of horrible.

And then when I came back to Toronto in May of 1978 after having sort of a rapprochement with my father and mother—they weren’t too pleased that I did this whole sojourn out West—I had this big meeting with my dad where I said, “I want to be an actor,” and he said, “Okay.” My dad was a lovely guy. I had great parents. But he was a conservative shopkeeper, and he said, “Look, I don’t know how to help you as an actor, but if you want to be an actor, give it a go for a year. Get a job. And if you don’t get a job, then we’re going to reevaluate and you’re going to go back to school.” And I thought that was a fair thing.

The next night, I was in Toronto, I’d gotten this crummy apartment, and I went to Second City, because I’d remembered the touring company, and the improvisations were free. Well, that night, John Candy, Martin Short, Catherine O’Hara, Gene Levy, a guy named Peter Torokvei, and Steve Kampmann, they did the improvs. And I think I went to the improvs for the next three months. Every night. And not only that, but I started doing workshops the following week, then I became friends with the actors backstage, after the show, at the bar. I had a revelation: “I want to do Second City.” This happened very rapidly. They were shooting SCTV, and I volunteered to become an extra, because they took kids from the workshop, so you can see me in the early SCTVs. I steal water from John Candy, dressed as an Arab, in the Bob Hope Desert Classic, and all this stuff. I’m very young, but I’m in there. So that’s where I met the producer Bernie Sahlins.

My mom was an American, so when I was pricing records in Vancouver, I remember calling her up, saying, “Mom, can you help me get my U.S. citizenship?” So with that in mind, I met Bernie Sahlins and said, “I’d like to audition for Second City Chicago.” He said, “Are you ready, kid?” I said, “Yeah, I’m ready. I’m ready!” So he said, “I’ll give you a call.” So I gave him my phone number, and he never called! So I called my parents a couple of weeks later and said, “I need to take a Greyhound bus to Chicago, because I’ve got a job offer at Second City.” Which was entirely an untruth. [Laughs.] So my dad—God rest his soul, I love him—gave me his credit card, and I took a Greyhound bus to Chicago and surprised the hell out of the Second City people, including Bernie.

But they said, “Okay, you can audition,” and the story’s much longer than this, but basically I auditioned with this wonderful guy named Mike Hagerty—we’re friends to this day—and they offered me a job. So I called my mother up, and I said, “Hey, Mom, I got the job!” And she said, “I thought they already offered it to you.” And I said, “Uh, yeah, but I had to sort of secure it…?” And she said, “Well, there’s an envelope here from the U.S. Consulate.” I said, “Open it!” It was my passport. Goodbye, Canada. Hello, world! And Linda Ronstadt’s Living In The U.S.A. was No. 1 the day I moved to the U.S.! [Laughs.] I never looked back. You know, John Candy was a huge influence on me and a loving, wonderful teacher. A great dude. I miss him terribly.

You mentioned him a moment ago, but how influential was Del Close for you?

Del Close by that time was more myth than man. And he was great, but he had a difficult time at Second City. He and I had got along personally, and I learned a lot from him, but I’ve gotta say that he, uh… [Long pause.] You know, I can’t exaggerate: There were things about him at that time where people were having some difficulty about him. And it was perhaps mostly because of his proclivities. And we’ll leave it at that.

But Bernie Sahlins, the producer of Second City, was a big influence on me. And Fred Kaz. And Joyce Sloane, another producer of Second City, was a huge protector and a different sort of influence, helping with my career and career guidance. And Del was in there. But I have to say that Bernie was a big influence. And Fred was as well, because I was and am very musical. In fact, we’re mixing “Don’t You (Forget About Me)” right now. I covered it for my new album. So Fred’s still in my life on a daily basis. They all are.

I remember Del saying to me backstage one day during the summer of the big Dallas cliffhanger, “I don’t know who shot J.R., but I know who shot up J.R.” And I was, like, “Oh, great, Del, thanks.” Because he and Larry Hagman used to do heroin when they did The Nervous Set off-Broadway in 1959. I was, like, “Oh, really? I want to hear this?” [Laughs.] The first day of workshops… I’m, like, 21, and they made us do workshops with Del. He goes to the edge of the stage, he takes off his clothes, and he’s there with this brown underwear on that used to be white, and his body is like a moon landscape with pock marks from where he shot heroin. And he teetered at the edge of the stage, and he said, “This… is my track suit.” And like Jesus Christ at the end, he spreads his arms out, and then he does a dead drop off the stage. And we all scramble to catch him, which we did. We’re all holding him by pieces of skin and hair, and as he’s, like, an eighth of an inch from smashing his head on a table, we caught him. And he looks around, with everything hanging out, and says, “Now… I can trust you.” Yeah, okay, Del. [Narrating.] “Dear Mom and Dad, today I met a member of the counterculture…”

You know, to date, I have never been let down by asking anyone about Del Close.

[Laughs.] Oh, I’ve got more and more stories about Del, believe me. He was, uh, certainly somebody you could react to!